By Dylan Smith

Spitgum sprawled down the hillside like the shadow of a falling tree. Telescope in their one hand, my walking stick in the other. All along the way they stopped in bright clearings to peer out at the shapes of distant leaves and at the bodies of darting birds, and they asked me a lot of questions. What’s that bird’s name? What tree’s this? My fever blazed and flared in the late morning light, yet I couldn’t believe how clearly I could see. To reveal, to uncover, to unveil, I thought. I put my sunglasses on. Did my best to answer Spitgum’s questions. Dragging the heels of their boots down the hill they had kicked up trail dust and now it settled into hollows of woodbine ivy and wine berry brambles, the air all aswirl through streams of sheer light. That’s when I noticed for the first time how the leaves of certain trees had curled inward, burning a yellowish red. Drought-sick, I thought. Or like a kind of blight. I touched the trunk of a rock oak tree. Identified the call of a wren. Spitgum babbled on and on about nothing. I felt drought-sick too. I could feel the birdsong vibrating in my hair.

Arriving at a ridge halfway down the hill I noticed what looked like a ribbon of wood-smoke rising up from a field just south of the farmhouse. Art was walking slowly down the freshly mowed slope, a five gallon bucket full of tools in his hand. In the other was a plastic gallon jug of water. Alma’s garden gate gently opened in a gust of wind and I scanned the landscape searching for her, tracing the tangle of wisteria vines along the winding road, the tall swaths of summer flowers leaning over stone paths as they dove down and snaked around the farmhouse and woodshed and the garden. A rain cloud had gathered above the sloping fields. Art took off his hat and stopped to rest at the stump of the lightning struck black locust tree, his body no bigger than my thumbnail. I could picture the tree even though it wasn’t there. Apple. Purple. Fountain. Paint. The rain cloud came apart. Art looked up into the absence where the tree had once provided shade. Saw us at the edge of the wood, waved, and walked on. Spitgum led me down into the field and we met Art standing by his van in the shade of the barn.

“Didn’t Hippie just mention something about a fire ban?”

Art looked up from the messages on his phone. His phone is a Samsung Galaxy. It looked like a tiny stone tablet in his hand.

“That’s not a fire, Sunshine. What you see up there is worter.”

“Water? Up out of what, the well?”

Art set his phone on the dashboard with some dark green gloves, then he opened the van’s side door to unload his bucket of tools. “Just west of that well’s a quick-coupler. Like for hoses. Found this cap shot way out into the field. I guess the pipe must’ve burst once I got the water back on.” Art turned to show us the metal cap. It said Rain Bird on it. Spitgum snickered. “First thought was maybe I’d run something over with my mower. But the situation seems more mysterious than that. Look at all that pressure, Sunshine. Never seen anything like it. Must be something to do with the hydrostatic pressure of the ground. Like at Yellowstone, you ever been to Yellowstone? I hear springs out there bubble up all scalding hot from magma. At least in our case the farm water’s cold. Cool clear worter. Just mysterious is all. A mysterious mist. Looks like we won’t be needing the telescope, Spit.”

“I’m so grateful for the mystery,” they said.

Spitgum and Chris have the same exact smile.

Art looked at them and laughed.

“Anyway, Sunshine — I’ve got to get going in a hurry. Emergency call just came from up on the mountain.”

The van with all its black and blue graffiti shone purple in the barn shade glow. Art slammed the side door shut and handed me the empty bucket. It took me a moment to remember which mansion he meant when he said up on the mountain. Art looked at the sun. Nearly noon. Then he ducked into the dark of the barn.

Spitgum kicked a rock and followed it out into the road. Picked at a runover snake with their stick. I took my dead phone from out of my pocket. The screen was cracked badly, but I thought it should still work. I plugged it into the charger I leave in Art’s van and noticed a giant book on the passenger seat. It was Lumbersweeney’s copy of Capital Volume 1 by Karl Marx. I had no memory of stealing the book. It still had his highlighter in it. Art emerged again with the jug of fresh well water and a plate of microwaved pizza from the night before. The two inverted phases of the movement which makes up the metamorphosis of a commodity constitute a circuit: commodity-form, shedding off of this form, and a return to it. Grease threatened holes in Art’s paper plate already. Spitgum’s shoulder blades rose up into the light like demon wings, or maybe angel wings, and I felt increasingly sick.

“The wren came back,” Art declared. He handed me the jug of water. I took a long drink, and then I pointed up toward the well with Lumbersweeney’s book.

“You’re saying that call is more of an emergency than this?”

“Correct. It’s their furnace, Sunshine. Bad oil leak. And there’s nothing to be done here for now. Those fields will happily soak up all the worter. Let me show you the work I have planned for you at Diane’s.”

Spitgum and I followed Art to the north side of the barn where the truck and tractor had been parked in the sun. I looked up the hill through the field toward the well. The fountain spray looked like a kind of endless explosion outside the farmhouse. Art had leaned several shovels against the truck along with two iron prybars for rocks and two posthole diggers. I loaded the tools into the truck while Art stood there eating pizza. Spitgum had already wandered off again and was looking into the back of my Volvo, their pink skull pressed against Chris’s in the glass. I sighed loudly and wiped the sweat off my face with my shirt.

“I went to Diane’s this morning and marked out where I want these holes.” Art lowered the tailgate and flattened out a piece of paper. A drawing in red pencil of Diane’s yard and house. “About a half dozen holes. You’ll see the red paint in the grass. I also marked the handles of these shovels here for your height. You’ve got concrete form tubes too. Those are in the barn. For the footings of the deck. Just do your best, Sunshine. There will be rocks.”

“Yo, Billy—what’s up with this CitiBike back here? You steal this thing or what?”

I locked eyes with Art through my sunglasses. He shrugged as if to say, What the hell’d you want me to do about it? I’d forgotten all about that bike, the city. The Tarot Card Guy named Calder and all the things I’d taken from Chris.

Daylight glanced off the body of Art’s truck. I went to pick at some rust at the bottom of the tailgate where it joined with the busted light, but stopped myself. Art saw me stop and smiled. The truck was essentially disintegrating, falling apart. Everything was. I almost said so, but I couldn’t bear to repeat the same old endless conversation about chaos and entropy and the truck, its low mileage in spite of the rust, all that salt they spray on the roads in winter and on and on and on and on. My fever deepened like a cave. Entered the bones of my back. I folded Art’s drawing into Lumbersweeney’s book. Art had fixed the busted taillight with some see-through packing tape and red spray paint. I could still see the rock Spitgum kicked into the middle of the road. It was the size of a little dove.

I ran a cold hand trembling through my long wet red dirty hair and decided it was time to lay down in the grass.

Art turned over the empty bucket and took a seat above me.

He chewed on his last bite of pizza. Wiped his beard with a rag.

“You drank too much again last night.”

“You’re the one whose eyes are all bloodshot,” I said.

“That’s just the dust. You don’t see me coiled up under no tailgate.”

“I was fine an hour ago, man. That kid did something weird to me.”

Art looked back across the lawn, chewing.

“I did nothing weird,” Spitgum yelled over my Volvo by the road. “All I did was fix the hater’s eye.”

“I have this fever now, Art. I can’t shake it. The breeze cuts through like November and all the leaves look red. You didn’t even ask if I wanted it fixed,” I yelled at Spitgum.

“You just feel sick because you’re scared,” Spitgum yelled back. “Bill went and betrayed his only brother and now he’s blaming me for the fact that he’s scared and lost and probably just sick from the guilt. Who would our Billy Willy be if not his brother’s half-brother? That’s a scary thought. Enough to make anybody sick. No — I’d come over and unfix your eye right now if it’s what you really wanted. But I don’t think it is, Bill. Pretty sure that would just hurt.”

“Come out from under there and let me see, Sunshine.”

Art nudged my busted rib with the toe of his boot until I came out from under the shade of the tailgate, groaning.

I took my sunglasses off.

“Jesus Christ — it’s an actual miracle. Barely a scar, Sunshine. Did you see your eye turned blue? The right eye’s still green, but the other one went fully blue.”

Art handed me the jug of water again. There was pizza sauce on his dark green shirt. I thought it looked like a blood mark. I drank the fresh water and poured some on my head and then I struggled to my feet to look at myself in the driver’s side mirror. Art was right. My left eye was blue. I immediately new that I liked it. Somewhere in the distance someone stopped shoving tree branches into a wood chipper. I hadn’t noticed the sound, but now I noticed the silence. Spitgum came up from behind me and I jumped. They had Calder’s wizard hat in one hand and a big chunk of green chalk in the other.

“And now, for my third trick, I will make a horse appear out of thin air.”

“Third? What the hell was your second trick?” I demanded.

But Spitgum stepped toward the side of the barn, fit Calder’s hat onto their shaved pink head, and with the green chalk against the red barn they drew another weirder, smaller barn, and inside that barn they drew a large strange green animal and a big green circle with wavy rays of green falling down on the animal like the sun.

“Horse,” Spitgum said, pointing at the horse and writing out the word. Art laughed and clapped. I was going to ask why the green sun had been drawn inside the barn with the horse — but out of the corner of my new blue eye I noticed a flutter of paper pinned under the windshield wiper of my Volvo.

I went toward it.

A letter from Alma.

Her handwriting wide and open and blue:

Hi — I want to write down these things which feel like the harder things before we see each other again in person…

Two black lumber trucks boomed passed the barn. The first swerved violently to avoid Spitgum’s rock, its six tires screeching as it burned marks onto the wavy blacktop road — but the other truck floored it right up over the rock and drove on as if it had been nothing.

I walked out into the road through a whirlpool of dust.

….hesitancy or space coming from my side is most likely a reflection of where I am in the circle shape, and not a difference in care…

Unthinkingly I picked up Spitgum’s rock.

…but my heart is still craving time to untangle myself from him so I can rebuild…

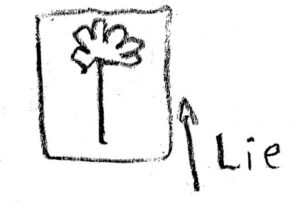

And that’s when I stopped myself. Folded the letter back up. I needed to be alone to read it. I took Spitgum’s rock back toward the barn where their picture had been wiped away already, and in its place Art was drawing a giant green illustration of the light spectrum while lecturing Spitgum with the telescope in his hand.

The diagram looked like this:

“Take this light inside Bill’s telescope for instance — we’re talking about just a sliver of what’s actually expanding beyond the visible eye. Infrared light, ultraviolet light. You want to talk about the mystery, Spitgum? Let’s talk dark energy, dark matter. Almost everything in our observable universe is invisible. Not to even mention space time or the speed of light or how with a serious-enough telescope, these scientists have seen all the way back through the fabric of earth time already. Right straight through to the very beginning of. I just heard it on the radio again today — I’m talking James Webb again, Bill — it’s happening as we speak. A telescope that can capture pictures of First Light.”

Spitgum took the telescope back from Art.

“But that would just be God,” Spitgum said. “You’re saying they took a picture of God?”

“Correct,” Art said. “Widen out far enough and we’re nothing but tiny particles in an unspeakable pattern of light that is everything. Particles of dust. I’ve seen videos of it on my computer.”

From where I stood I could see Chris’s two favorite trees. A pair of sugar maples which always merged into one great giant-looking tree in the window of Alma’s kitchen.

In that moment I wanted nothing more than to know what Chris was reading.

“You know Cain killed Abel with a rock,” Spitgum said, pointing at the rock with my telescope.

“Excuse me?” I said.

Just then Art’s wren landed in a barren patch of grass at our feet.

“Wow — there she is,” Art whispered. “Spitgum, look — she comes back every summer to nest on the sill above my saws. How was winter down in Florida little birdy? Bring us back any plastic from the beach?”

“I wonder, Bill — Do you think bodies decompose more slowly during drought years?”

“What kind of fucking question is that, Spitgum? What, are you threatening me?”

“No, I meant it from a scientific perspective. Seeing as all the worms are probably dried up.”

I experienced a sudden and confusing urge to injure Spitgum physically.

Fugitive. Mountain. Flower. Fist.

Instead I set the rock down slowly, picked up Lumbersweeney’s book, and then I started for the farmhouse.

“Sunshine, wait — I figured you would give Spitgum a ride to the church on your way to Diane’s. My oil leak is in the opposite direction. It’s coming up on noon. ”

“I’m not taking that kid anywhere,” I said. “First of all, Art, I already told you I’m sick. Second of all, just make the kid drive their goddamn self.”

“Ain’t allowed to drive no more, hater. Hence the whole reason why my meeting’s inside a church.”

Barn swallows swooped in and out of the barn, spiraling in the shape of an eight.

The wren wrangled up a living worm. Looked me in the eye. Flew away.

“Sorry, Art. But I need to go find Alma.”

I started for the farmhouse again.

“Wait — I have a deal for you, Billy Willy. Lend me that CitiBike, just this once, and I’ll get your Volvo running again for free.”

I turned back around.

“No,” I said.

“Look, Billy — Art says all your Volvo needs is a starter. That’s kid stuff. Let’s make this happen like a barter. You pay for the part and I’ll be your mechanic. Free labor for free rides on the CitiBike this summer. I’m desperate for a way into town. It’s a win-win-win for all three of us. Just like Marx.”

Spitgum presented their pale hand as if I’d shake it just like that.

“What do you know about fixing cars?” I asked.

“My best friend back in the desert’s a mechanic. Name’s Ever. I helped him here and there, could easily call if I run into trouble.”

I looked over at the Volvo. It looked like a bottomless pit of black dead moon water.

“Consider it fixed, Bill. Seriously. Let’s shake on it. Fair and square.”

Art laughed. Shook his head. Shrugged.

“Deal?”

“Whatever, man. Fine. Deal.”

After shaking my hand Spitgum said, “Ready to see what my second trick was?”

“No,” I said.

They reached out toward my face again and before I could get my hands up to defend myself they’d pulled a ring out from behind my ear. “Tadaaaaa,” Spitgum said. They dropped Alma’s engagement ring into my hand and broke off into a run toward the Volvo. Before Art could bend down to pick up his empty bucket they had already pulled out the CitiBike onto the grass, Calder’s wizard hat like two hands clasped into prayer atop their wild pink head.

“Kid’s a total trip, Art.”

“You got that right. Like the drum major of some kind of fucked up parade.”

“Battery’s still some life in it!” Spitgum shrieked.

Art had leaned over to look at the cover of Lumbersweeney’s book, his head almost upside-down to see it. It’s a dark painting on the cover. I showed it to him. Three men working in an old iron factory, a kind of spiraling white fire burning at the center of it.

“The Forge (A Modern Cyclops),” I read. “By Adolph von Menzel.”

“Looks like they’re working an old rolling mill,” Art said. “I’m guessing for the railroad tracks. See how they don’t have any eye protection? All they did back then was squint. No gloves either. That poor bastard doesn’t even have shoes. I guess some things never change, Sunshine. Reminds me of this old timer I knew back out in—”

“Shouldn’t you be heading up toward that oil leak?”

“Oh, shit. Yes. Thanks.”

I handed Art the water jug. He took a long, slow drink, then sighed.

“Everything returns to chaos, Sunshine.”

“I know, Art. I know.”

“Tell Alma I’ll be back down tonight to fix her worter.”

“Is anything reaching the house?”

“Nope.”

“Alright.”

After shaking my hand Art patted me on the back in a paternal way that actually made me feel a little better. Turning to go I heard the familiar quiet vroom of the CitiBike taking off toward the south, and turned in time to see Spitgum speed off shrieking for the church with my walking stick.

I walked up the slope through the field toward Alma’s well.

A storm had established itself above the mountains to the west, and that fountain beside the well looked like a tower endlessly falling.

Dylan Smith works at Brooklyn Botanic Garden and lives in a shared house with nine people and a Steinway piano the size of a boat.