By Dylan Smith

And so stumbling out through that bookstore drunk I had only the vaguest idea of where I might have left my bag. The grounds of the city’s biggest cemetery rose up on a hill across the street, with its gas lamps lit and its tall stone graves and these ancient trees edged in light as the path doubled back down along the hill, and I could see all the CitiBike baskets empty in a line. No bag. The bells above the bookstore door jingled as it shut and I worked to manifest my bag’s place inside my head. To envision it shimmering there behind our empty bottles in the Square—but I was also immediately suspicious of that motherfucker Chris.

Every bender we’d ever endured together had ended in me losing something like this. Whether it be my keys or shoes or pants or my bag, it never mattered—it always drove Chris crazy. Yet there he was, so perfectly serene. Stopping in the poetry section, even. So cooly detached. I watched him through the glass door with increasing suspicion. Flipping through some tiny pink book. Taking a wallet out of his tote bag to pay. I may not have known exactly how yet, but I knew. Chris was up to something—hiding something—and that something had something to do with my bag.

My Chris Book.

My journal. My secrets.

I walked across the street.

Chris came out of the bookstore smiling. Bells. I stood beneath a streetlamp in the lowly lit night. The cemetery’s perimeter wall was behind me and Chris had his tote bag open. He placed the new pink book inside it with the wallet, then his hand came out with a small point and shoot camera with a flash.

“Stay just like that,” Chris said.

He stood there behind the parked cars. A bright flash of light with a click.

Upstate it was pianos, I thought. Chris’s constant music. Now pictures. He squeezed between two parked cars coming closer. I rolled my eyes. Chris took another picture.

Click.

The flash was blindingly bright.

Click.

“That’s great, Bill. You really look like shit. That one’s going to be great.”

Click.

That horrible high-pitched sound after each flash.

Click.

I hit the camera out of his hand and went for his bag, thinking I’d run with whatever money was still inside it with his books, but I couldn’t see much because of the flash and before I could get my hands up to protect myself Chris slapped my face hard and hit me in the chest and then I was on my back with his palm on my head against the stone. Chris got right up on top of my body and now he was on me with his knee down hard against my upper rib, the rib right above my heart. I heard the rib go pop and I lost my air to the weight of him. I spit up at him and growled and told him to Fuck off man stop it come on man stop, and I was wheezing. Chris stared down at me cold and calculated and quiet. The sidewalk felt cold too and as hard as the frozen path up to my shack in winter. A moment’s pause while Chris figured out what to do, his palm in my face. If there’d been a rock nearby I think he might’ve done it. He shushed me. I wriggled around. Then his phone rang.

Hallelujah. Haha. Church bells. I laughed into the palm of his hand.

Chris got up and spit into the roots of a sycamore tree. Took out his phone. The little bells inside there rang and rang and he took in a full breath. It hurt me to laugh, but I was laughing.

“Sarah—Wow—Hey, man. What’s up?”

Chris stepped over me. Walked up the street.

I had hit the back of my head pretty hard and so I just lay there some more trying to think. Up high in the sycamore tree I saw a blue tarp caught in the tree’s lamplit canopy of leaves. I tried to concentrate but I couldn’t. I gently elbowed myself back up against the stone wall of the cemetery and dragged my way back down toward the tree. Still wheezing. The roots of the tree had really wrecked the bluestone slabs of the sidewalk and the slabs rose and fell in the shadows like a prank. Art once told me how the city’s sidewalks had all come from bluestone quarries in the mountains around Alma’s farm. A hundred and thirty years ago. Each slab of bluestone seemed so heavy, I thought. The incredible slow strength of that sycamore tree and its roots. I wondered how many people it took to lift the slab I lay on. The blue tarp must have blown up into the tree in winter, I thought. Some poor bastard’s blue shelter. I could hear Chris speaking lowly into his phone up the street. Some poor bastard’s blue tarp house. The maple looking leaves of the sycamore tree had grown and greened all around the blue tarp but I pictured the sycamore bare of its leaves in winter. I closed my eyes. The night was hot and still and the air was wet and heavy. I could barely breathe. I imagined the tarp flapping up there in the wind in winter and the thin trembling branches. It was a cold blue wind and the tarp flapped and flapped up high and the flapping was the sound of my fate, my defeat.

Chris came back down the street nodding and listening to whatever Sarah said. He stood over me looking crazy. All wild-eyed and high. He walked over to the camera and picked it up. Looked it over. Put it back in his bag. In the sky I saw isolated stars, distant and apart. Not a single constellation. We were down there way below the graves. I hadn’t noticed before, but Chris was wearing these fancy reddish brown leather shoes.

“Right,” Chis said. “I know—Yeah he’s right here. Right. We’re having a blast. Bill’s little birthday party. I know. Yeah. Right. Exactly.”

That’s when I finally got up. My breath had come back a bit but not fully because of the rib and I started to walk up the hill toward I didn’t even know where. The subway, maybe. The Square. Chris followed a little ways down the hill until he hung up and then I heard him running up the hill behind me in those shoes.

I stopped and turned and pointed at him.

“Get away from me you crazy piece of shit.”

“Oh come on, man. You’re who came after me. We overreacted. We were high. Let me buy you a drink.”

I kept on walking. Chris followed, but not too close. The shoes made him sound like a horse trotting up along on the stone. I wheezed a little as I laughed and walked and I was still pretty high and then a beer started to sound pretty good. The bar was a dive we’d never been to together. A place with ripped red leather booths and a jukebox and mirrors. Chris ordered two cans of cheap beer with shots and then he told me, “Put out your hand.” Four blue pills fell into it. I kept my hand out. “Fine,” he said, and then it was five pills and then six and I said, “Hand me that pink book.”

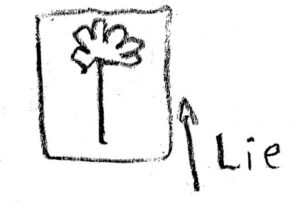

The bathroom was as dark as a cave and the walls were thick with language. I smashed two pills on the hardcover book and there were layers and layers of stickers on the wall, stickers thick as stalactites, and a big green tag above the toilet looked like this:

Which forced me back into contact with my dilemma. Which was that Alma had made me whole. Before her I hadn’t even known I wasn’t. I’d fallen in love with her wildly, madly, and I’d lied about it all to Chris. I cut two blue lines on the tiny pink book. Love poems by like Neruda or somebody. Alma with that film guy and all my own poems gone missing. My Chris Book. My secrets. I snorted up the lines off that tiny pink book and when I came back out Chris had scribbled an address for me on a napkin. “Sarah’s,” Chris said. I could barely read it. The ink was pinkish red and his camera and wallet were there on the bar and his tote bag hung below him from a hook.

I stared at Chris’s scar.

“You’re who came after me.”

“I know, Chris. Go fuck yourself.”

“I have to be at work in the morning.”

“Okay.”

“You left it in the Square right?”

“That’s what I thought too. But by now somebody probably took it.”

“Where’s your car key?”

“My pocket.’

“What about a phone?”

“It’s been dead a long time in the duffle bag.”

“Well I’ll be asleep by the time you get back. Just ring the buzzer until I wake up. We’re meeting up with Sarah tomorrow, man. Uptown at this address when I get off from work—it’s where your Volvo’s parked. I figured you can drive it back upstate from there. Just please come back to my place tonight to shower before you meet her, Bill. I’ll have the couch made up for you. Some clean clothes set out. You need to try to get some sleep.”

“Okay.”

“Are you hurt?”

“No. Just my rib.”

“What about your head?”

“That’s fine.”

“Alright.”

“Okay.”

We took the shots without a cheers and I handed Chris the book and then he wobbled his way back past the jukebox toward the bathroom. The bar music blared yellow white red and the bar itself felt hot and wet and red. Chris had taken his tote bag with him but he left the bottle of pills on the bar with his wallet and camera like an idiot. I folded Sarah’s address and stuffed it into my pocket. I thought about the green tag in the bathroom again and about the blue tarp flapping in the wind—and then I thought about the first load of firewood I ever helped Art deliver to Alma’s farm. A big blue truck bed full of red and white oak. I helped Art unload it into a pile in the autumn grass and we covered the pile with a big blue tarp. I heard Art tell Chris we should stack it all in the woodshed, but nobody ever did. Every morning all winter long I’d wake up at dawn and walk out hungover through the frozen field toward the small stable barn where Chris once kept his chickens. Four roosters and fifty spent hens from some guy Chris found on Craigslist—I had to feed them as one of my chores. Usually I’d find only two or three eggs and on the hike back up I’d fill the blue wheelbarrow with wood from under the tarp and wheel it all up toward Alma’s farmhouse to make a fire. I’d put on a pot of coffee and sit at the kitchen table alone by the window writing poems. Alma would wake up. Come out with a cute wave and make herself some tea. We’d sit together by the fire in the bright silence and she’d be reading. One morning I watched her paint the wood pile. A small abstract kind of thing on a piece of scrap cardboard I’d ripped up for kindling. Four or five woody red wiggles and a blue line up above like a wave of water for the tarp. I loved that picture. I hung it up in the attic above my cot. But that winter one of Chris’s heat lamps got knocked into the hay because of the wind and when I walked out into the field at dawn the stable barn was burning. Hundred year old chestnut. Ancient hand hewn beams. All fifty of Chris’s chickens in it, and nothing to be done. The frost had thawed in a ring around the fire and the flames rose up with the sun like a silent red hand and I just stood there by the wood pile watching the morning burn.

At the very last second I decided I should leave. Fuck Chris. I grabbed the bottle of pills and Chris’s camera and the wallet and I ran out into the heat—I ran and ran and ran into the night and I didn’t want the bastard to catch me so I held my busted rib and I ignored my throbbing head and I was in love and I ran and ran and then I was underground, and at the far end of the platform hidden under the stairs I waited for the train in that long white yellow blinding miserable airless summer heat.

A little time passed.

A lot of shallow breaths.

The subway tile pulsed with my throbbing head and glistened. Red rust trickled between the tracks in a little creek and everywhere the trash and stink and the rats. This kid came down the stairs in a paper birthday hat tugging at a big bouquet of rainbowy balloons. I stepped out from under the stairs and yelled, “It’s my birthday too,” but I must have scared the kid’s mom because they rushed away and down to the other end of the station.

That’s when I saw this guy standing alone and staring up into the light. He looked as if he’d just seen something horrific, or maybe holy. The guy was draped in white robes which time had darkened with grime and in that underground air he held out a Dunk’n Donuts cup as if it were filling with the light. I took out Chris’s wallet. Almost a hundred bucks. I removed two twenties, balled them up as I approached, and I dropped them into the guy’s holy cup. Unmoved. I put Chris’s driver’s license in the cup and one of his credit cards in there too. The guy’s dry lips quivered. He muttered something under his breath—not a thank you, but more of like an underground prayer. A manifestation of everything dirty and divine. The fluorescent light filled him as it flickered but the man remained true. Unmoved. Then the train came and I got on it and it was like the gates of hell clanged shut behind me. The gates opened and shut and they opened again and opened and opened and opened again and it was like that all the way until the bridge—and then soaring through the air again clanging and clanging and there was the city and the dark black water and the night again, and the Statue of Liberty like some holy golden light out there in her money-colored robes and the city pulsed and sparked and each window replaced a star in the night, and then I was up in the Square and I was searching for my bag alone in the dark and broken.

It wasn’t there. Simple as that. I checked under the chiseled rock bench and kicked around at the empty bottles Chris and I had left behind—but nothing. I checked trash cans and inside tree holes. No bag. No bag anywhere. By now it was getting late and the Square had emptied except for the people who lived in there under tarps and a dozen or so drunk college kids stumbled around being idiots. Anybody could’ve taken it. I couldn’t even find the moon. I walked around the fountain looking for the guy who’d been painted to look like a statue but I didn’t see him. I sat back down on my bench to think and listened to the sound of the fountain. I had a little moonshine left, but not much. I drank it down. A drunk piano player played sloppy drunk songs in the bottom left corner of the Square but I could barely hear him over the water. A newspaper blew by like tumbleweed. Moved by some mysterious gust in the strangeness. There was the red chalk again. CURRENT. I chewed on one of Chris’s pills.

And that’s when I saw the Tarot Guy sitting there crosslegged under the Arch. He’d set up a squat foldable table at knee height. He sat there shirtless and he was staring at me in this tall gray wizard’s hat. I waved, but he didn’t move. He really freaked me out. We eyed each other. The wizard hat was the size of a traffic cone on his tiny bald super-tan head but there was a lot of calm air around him as I approached. He seemed to be looking out at me from within a deep meditation.

A hand drawn sign taped to the table read: FORTUNE TELLER. CALDER. TAROT. TEN DOLLARS.

I waved again. Nothing.

“Hey man—you know that statue guy? That guy painted silver and gold who stands over there like a statue?”

“The man you speak of has a name. It is Gary. Gary is a good friend of mine. So yes, I have seen him, but he is gone.”

“Well have you seen a duffle bag? I’m looking for my duffle bag. I left it over there under the bench.”

“Oh. Ha. Yes. It’s you. Of course. I’ve been waiting.”

Calder pulled my duffle bag out from underneath his tiny table.

Holy shit. I dropped to my knees and held my busted rib. Magic. My broken heart. I opened the bag right there on the spot and dumped its contents onto Calder’s tiny shitty table. I tried to say thank you but I could barely breath. There were the socks and the underwear and the long red birthday box Chris had given me and the card. All of it was there in a pile on the table. I dug through the bag some more and found some loose flattened papers and some trash and a dirty broken toothbrush and two pens. I pushed through the two pairs of socks and the underwear on the table, and I pushed everything off the table and onto the bluestone slab and looked through it again. I ripped opened the red box. Inside it was a telescope. A golden telescope with a leather strap like the kind a sailor would use to find land. I picked up the box and dropped it again and I opened the bag again and all its side pockets and I held it upside-down over the table and I shook it out. Saw dust fell out over everything and some small rocks and a gum wrapper and a couple bottle caps. I picked up the long red box again and I threw it off to the side at the Arch.

Calder watched closely.

“I’m fucked,” I told him.

“Yes.”

My Chris Book. My journal.

Calder nodded calmly. Knowingly.

I couldn’t figure out how exactly yet—but I knew it too.

Chris had stolen my secrets.

For money Dylan Smith plants flowers on rooftops in New York and has a website with links to other stories online. Oh and check out The Other Almanac. A piece of Dylan’s will be published in print with them this fall.