By Dylan Smith

June 21

Catalpa flowers fell like thwack outside the lumberyard. Burnt to brown mush on the pavement. Mountain laurels blooming too, starlike pink flowers streaming all along the road into town. While Art paid for the wood I played fetch with the lumberyard dog. A giant black shepherd named Blue. I threw catalpa sticks for her at first, then rocks. Blue loved rocks. I had the birthday card from Chris in my pocket and decided to sit against the catalpa tree to open it. Low dark rolling sky. Blue there beside me panting happy in the grass. We both needed water. All the trees in town did too. On the card was that painting Chris mentioned from his museum, the portrait of Saint Francis by Bellini. We’d talked about going there together to see it. In the painting a barefoot Saint Francis has just stepped out of his cave and into a holy light. It’s a divine light, a metaphysical light, and Saint Francis is in ecstasy because of it. Eyes rolled back into his dirty balding head. Saint Francis has accepted the light, become the light, he is spreading the light around—and now the landscape is illuminated too. There’s a walled off city up above him on a hill and in the valley between this city and Saint Francis there’s a heron, a donkey, some barren trees and a spring. Thwack. A tiny amphora to gather the water. I strained my swollen eye to see it. Behind Saint Francis there’s a poetry desk with a red holy book on it and a skull—and reproduced so small you can barely see it thunk thwack, there were dashes of red paint on his palms. I looked up. Leaves as big as bibles dangled in the heavy air. Thwack. Man, I love that little donkey. Heat lightning in the distance. The mountains looked like paintings of lakes.

I turned the card over. Chris had written this:

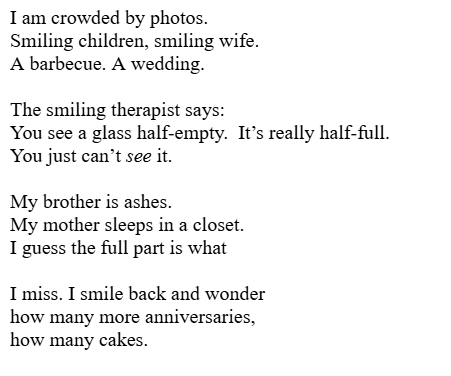

Bill— There’s this sticky note I found the night you helped me move out of Alma’s. It reads: FROM DANGER GROWS WHAT SAVES. I can’t remember where that quote came from. Do you? I don’t even know which one of us wrote it. I’ve been thinking about that night a lot. You talked about getting older. How the edges of things have gotten rigid. Crystallized, you said. Static. I remember the days when your birthday meant it might as well have been mine too, when the borders between us were blurry and weird. I’ve been grieving those days lately. It feels like one of us is dead. I think this sticky note has something to do with it. I wonder which one of us wrote it. —Chris

Blue pawed at a waterless rock. Looked blissfully out at the mountains. Wisps of smoke rose up from the fallen flowers, dispersed like spirits above the pavement. Hair of the dog would’ve been good about then. Good dog, Blue. Flowers like heaps of dog shit steaming. A shiny new red truck pulled into the lumberyard lot. Parked beside Art’s van. A man jumped down, went into the store. Red neck left his red truck running. I walked over. Looked inside. Another dog sat there, smiling, the AC blasting through his wavy grizzled coat. I opened the truck door just to feel the cool air. Stench of stale beer, carnivorous farts, cigarettes. The seat covers said God Bless America right where you would sit and the radio was on. I turned the voices up. Cattle dropping dead across America for the heat. The dog looked at me kindly, knowingly, trusting, a sage. I hoisted myself up into the driver’s seat. God Bless America. I just wanted to pet the guy’s dog.

Cell phone in one cup holder. Bottle of water in the other. A firefighter radio had been mounted to the dashboard, and the guy’s cell phone background was of him knelt down beside a giant dead antlered deer.

First water I’d had all day. I unscrewed the plastic bottle. Took a long drink.

That’s when Art appeared in the truck windshield, grinning. Sheets of yellow inventory paper in his hand. He pointed at the van. I said goodbye to the dog and jumped down.

“I know Blue, I know, you’re a horse, I know, go find yourself a rock,” Art said.

Art’s van is like a mobile barn. Piles of spare plumbing parts, chords and rope and saws, screws everywhere, random scraps of dry wall and wood. The white paint is all tagged up from when Chris and I took it into the city for a job. Now Art rarely drives it to town anymore, only when we need to load it with lumber. The van must be a little longer than the truck. I climbed in. We’d already gone to the hardware store and Alma’s new well pump sat in a box at my feet. A marked light fell in through the spraypainted porthole window. I started to turn through the radio stations.

“That took forever,” I said.

“Kid working the register wouldn’t know a hawk from a handsaw.”

Art dug around behind himself and pulled up a box of Beck’s.

“I think you just quoted Shakespeare,” I said.

“No shit? My old foreman used to say that all the time. You sure that’s Shakespeare?”

The red neck came out of the store with a drooping plastic bag. Nodding and waving at Art.

“Pretty sure it’s from Hamlet,” I said.

“Wow—I guess that’s what happens when your apprentice is a poet. Quoting Shakespeare is so boojswhaaa, Sunshine. I feel like a weekender.”

“These beers are going to be hot as shit.”

“Hot beer is better than no beer.”

Art sawed the air with his hand to let the red truck back out first. The guy waved again. Gave us a thumb’s up. I thought he looked like a cop. But Art was holding his beer out above the dashboard now, cradling the bottle before him like a skull.

“To Beck’s, or not to Beck’s,” Art yelled, laughing. “That, Sunshine, has always been the question.”

Art drove us up the dirt path toward the lumber.

“Goddamn,” I said.

“Yes. ’Tis the Devil’s Temperature.”

Blue was up there howling at us. I poured the rest of the red neck’s water into a bowl for her as Art backed the van into one of the outbuildings. Loading the lumber took a long time. Art talked about wood grain being growth rings. The lighter wood grows in spring, Art said. The darker part through the fall. Tighter rings mean drought years. Metaphase. Anaphase. Telophase. Less water means less growth. When we finished loading the lumber Art threw a couple rocks up the hill for Blue. Lightning, nearer, split the sky apart—then thunder. Blue galloped back down toward the store. Goodbye, Blue. It was getting pretty late in the day. Nearly night. The lumber was longer than the van by a foot, so Art strapped the back doors to the boards with some rope.

“What’s this wood even for?” I asked.

“I’ll buy thee a pitcher of beer if you help me unload it tonight.”

“Unload it where?”

“Property back up toward the farm. You’ll know it. We’d be going in for pizza and beer at the Country Inn first.”

“Yes, Art,” I said. “God, please, yes.”

Art stomped the fallen flowers off his boots as we entered the Country Inn. Chainsawed black bear sculptures by the staircase. Peonies in glass jars opening softly wild in the lamplight. In the mirror above the mantel Art removed his dirty hat and waved it at the two locals drinking wine by the dining room window. Lily pads on the dark pond water. Purple yellow mountain flowers muted in the murky light. Beyond the pond I could see Diane’s house tucked up into the darkness between some trees, the faintest red fluorescent smear of her electric car, and the local women waved back warmly as Art and I maneuvered our way around empty tables toward the heavenly lavender light of the bar. My comfort forever in that lavender light, the red and blue neon entwining. Even if it was Chris’s drug dealing theater friend Lumbersweeney behind the wooden doors, a book between his knees, highlighting something in the high and silent holy. I put my sunglasses on. Conrad was hunched in his usual corner spot against the wall, staring another knot into the bartop. Behind him a beer sign burned with wild horses and there was an empty stage framed by red curtains beyond the red booths—and now kicking through the kitchen doors to our left entered Donna with a tray of pasta and salad and fish.

“Eyes up, Sweeney,” Donna hollered down the bar. “Anywhere you want, fellas.”

Lumbersweeney dropped the highlighter into his book and stood, smiling.

“It smells like a chainsaw in here,” Art said.

“My Hippy’s trying to fix a broken toilet,” said Donna, smiling too, and then she disappeared back behind us with the food.

Lumbersweeney placed a cold Beck’s on a coaster for Art as he put back on his hat.

“A Sloop for you Sweet William, our poet, my long lost friend?”

“Thanks Sweeney,” I said.

Lumbersweeney brought down a pint glass from above and poured me the needed golden nectar. Lean arms smeared dark with old sailor tattoos, his mustache black as two raven feathers. Poor old Conrad had just noticed we were there and, frowning, he was struggling to get a surgical mask onto his face. The sounds coming from his mouth made me think of a reptile’s eyes wetly blinking.

“What book you got there, Sweeney?” Art said.

With one hand Lumbersweeney set down my pint and with the other he lifted up from below a brand-new-looking copy of Capital Volume 1 by Karl Marx.

“Jesus Christ,” Art said.

“Either of you ever read it?”

“I tried to once in college,” I said.

“Well let me tell you, Bill—the dude’s critique is clicking for me on every level. I know our Anarchy Book Club went to hell as soon as Chris left but I’ve stuck it out through the first three chapters and now I’m finally seeing the shape of it. Funny you two should walk in on such a night—I literally just got off the phone about it with Chris.”

“You talked to Chris?”

“Not an hour ago, Bill—you should know he’s been trying to get ahold of you. Sounds like you two had a hell of a night in the city. I’m sorry I missed it. Chris seemed awfully concerned about where things stand with you considering what with all the drinking and drugging and the sneaking away with all of Chris’s stuff and such. Classic fucking Bill, I said. But you should call him up, settle the score—you can use my phone if you need it. Anyway, I convinced him to come back up here for the party we’re throwing on the Fourth.”

“Wait, Sweeney, what? Come back up where?”

Art chuckled.

“Up here, Ol’ Bill. To the upstate country. Of course taking into consideration the unfortunate location of your shack, I mean seeing as it’s on your almost-sister’s land and all well I offered Chris my futon down the road—and then of course Hippy being Hippy, he offered Chris a room upstairs for the night, and that was that.

My eye throbbed badly with all the blood that had rushed to my head. I looked down at my hands. They were vibrating like the prongs of a tuning fork.

“I’d like a shot of something,” I said.

Lumbersweeney poured out three shots of whiskey and we took them. Conrad didn’t get one. He made more noises with his mouth.

Lumbersweeney went on:

“Art—I’ve actually been looking to run into you. Day after the party here I’m hoping to throw another Hangover Wake for myself—Hippy agreed to help refurbish the old Coffin, but I’ll be in need of your and Bill’s tractorial assistance beforehand what with all the digging and lifting and of course with the ceremonious lowering day of and such. Have you time for that?”

“You got it, Sweeney,” Art said.

I chased the shot by drinking slowly and intently my entire pint of Sloop. Then I lifted my sunglasses up into my hair.

“Christ, Bill—what the hell happened to that eye?”

But barreling out from behind Conrad’s back came Hippy Quick careening out of the bathrooms with his bare summer arms outstretched and that tremendous dirty wizard’s beard yelling, “Saint Art! Speak of the Devil himself! The very man! Hallelujah!”

“Heya Hip,” Art said.

Hippy rounded the bar like a bear and swung an arm around Art’s neck in a kind of giant violent loving hug. Sawdust and pitch in his beard, the sleeves ripped off his ruined flannel shirt. That’s when I noticed the pipe wrench in his hand. In the mirror behind the bar Hippy set down the pipe wrench and reaching over Art’s beer he took the bones of my hands so tiny into his, and he shook them. “Does me damn good to see you two drinking beer in here tonight,” Hippy said. Glasses goggled the sea glass green of his eyes. I looked away. Saw myself. My nose had turned bright red from the whiskey. If all of Art is supposed to be a mirror held up to Nature, and Nature a mirror to the Divine, then why do I always look so fucked up and broken?

Blood, I thought. Bloody blood blood, blood.

I lifted up my empty glass. Hippy really did smell like a chainsaw.

“Get these men more drinks, Sweeney, and some pizzas—you fellas want some pizza?”

“Have a whiskey with us Hip,” Art said.

“No, no.”

Lumbersweeney poured a few out.

“Come on Hip,” Art said.

“Unfortunately it’s been deemed Dry Weekdays around here, Art. Donna’s orders, unfortunately.”

“Trouble again?”

“Trouble? Me? No, look—I’m a grown man. A grown man must consent to being in trouble, Art. I’ve consented to no such thing. Trouble, no—nothing like that. It’s more like. Well. Yes. Yes, I suppose you could say I’m in some kind of trouble—but anyway, look—it’s no matter fellas. You came in on a perfect night. Sweeney here was just giving Ol’ Conrad and myself a lecture on what was it again, Sweeney? Hegel’s goddamn what?”

“Dialectic,” Sweeney said.

“Jesus Christ,” I said.

“Just give them the quick of it, Sweeney—get a load of this, Art, it’s fascinating stuff—Sweeney, start with what you were saying about The Absolute.”

“I need another goddamn drink,” Conrad said.

I took my shot. Sweeney took his too.

“I’m trying to remember when the last funeral for you was, Sweeney,” Art said.

“Going on three years now, Art. That was the Halloween Wake. A lifetime ago, it seems to me.”

And all at once I remembered Chris at the bottom of Alma’s stairs smiling up at me in the morning three years ago hungover. Our first time visiting Alma’s farm upstate from the city—The Inn’s infamous Happy Birthday Art But It’s Also Halloween Party. All I remember from that night was Alma dressed up like the Holy Ghost, her two eye holes cut from a clean white sheet and on her head a nearly invisible wire crown holding aloft a golden glow stick halo, the way she lifted the sheet up to scream I’M THE HOLY GHOST at the locals with her perfect black eye paint streaming in the hot packed bar, and then it was the next morning waking up hungover and alone in Alma’s attic and the film guy who she’d eventually leave for Chris was there, I think his name was Sebastian or something, he was down there making breakfast for Alma and failing to build a fire and Chris was at the bottom of the stairs smiling up at me in his Evel Knievel cape saying Bill—we’re late for Lumbersweeney’s Burial—should we go?—and then it was the fresh wet mountain smell through the window of Alma’s car and a blur of dark blue fog through the gentle drift of morning—and I remembered the way Lumbersweeney had prepared people ad naseum the night before handing out pamphlets and explaining in all seriousness that his Coffin had been built to Divinely Inspired Dimensions, taking into consideration of course Celestial Mechanics through which the Coffin would by way of its decomposition Transfigure, transcending of course the limits of linear time and undergoing as it were a kind of Interstellar Odyssey through which it would gather its collection of Galactic Artifacts and bring back up from Below new forms of Interdimensional Residue, Lumbersweeney said—and it was explained at length how Lumbersweeney could not himself be in the Coffin per se but would as it were remain Above in order to attend the Wake and eulogize himself and in this way it would be Art—it was supposed to be some kind of Art—and I remembered the way Art himself was already working the tractor when Chris and I arrived, dumping cascades of beautiful black dirt into Lumbersweeney’s grave in that field above the pond with a small crowd of hungover mourners huddled over the hole in dark clothes and Hippy Quick was there in bright robes holding out a lantern which hung from his walking stick and Lumbersweeney with his hands raised on high in the not quite rain quoting Quod set supers set sick quod infers and looking wild, totally wild.

“I already made my plans for the Fourth,” I said.

Art laughed. Took his shot. Wiped his mouth.

“Plans, Sunshine? What plans.”

“You suppose there’ll be a fire ban by then?” Hippy said.

Lumbersweeney opened another Beck’s for Art.

“Absolutely. At this rate? I’m surprised there’s not one in place already, Hip.”

Conrad mumbled something jumbled to himself in the corner. Blue mask down around his chin. Legend has it that Conrad’s son died leaving The Country in a decade ago drunk. Last seen leaving with no headlights on. A deer. A tree. Dead son dead and gone.

Lumbersweeney poured me another Sloop.

“Conrad needs another too,” I said.

“I heard him, Bill. Will you free up by morning for my Burial at least?”

“Sorry, Sweeney, but these plans of mine extend out into the unforeseeable morning. You can send Chris my best though. I’m sure he’ll enjoy your grave little play.”

Sweeney slammed my beer onto the bar.

“Is there a problem between me and you, Bill?”

“Thesis. Antithesis. Synthesis,” Hippy said.

The pipe wrench was there on the bar beside his hand.

“Easy does it, Sunshine,” Art said.

I was staring at myself in the mirror.

“Won’t somebody please just get me a goddamn drink,” Conrad said.

But like an angel on my shoulder in the mirror behind the bar Donna entered again with an empty tray.

“Hippy, darling—run up and get that smart thermostat from off my desk.”

“Gentlemen,” Hippy said—the saloon doors singing shut behind him.

“Beers are on me if you can fix whatever’s wrong with our toilet, Art. The beautiful bastard’s been in there all afternoon. What might take him another day could probably be done in an Artful moment from you.”

“You got it, Donna,” Art said.

Lumbersweeney had subtly sidestepped to the other side of the taps and was lighting a tray of tea candles. I put my sunglasses on. Art entered the bathroom with Hippy’s pipe wrench and the beer.

“Alma called today, Bill. She wants to buy my kiln.”

I was unable to process that information. Donna came around the bar to wipe some glasses dry, but then she was there before me with her hands on her waist. Looking at me. She picked a piece of hay off my shirt.

“Take those goddamn sunglasses off and let me see,” Donna said.

“Oh come on, Donna,” I said.

“Let me see.”

She leaned in close to look.

“Have you had it looked at yet?”

“Just by you and the person who glued it.”

“Can you see out of it fine?”

“Of course I can, Donna. It just itches is all. And throbs a little. Like there’s dust in it.”

“Looks more to me like a plank,” Sweeney said.

My stool fell loudly behind me as I stood.

“Oh fuck you Lumbersweeney,” I said. “You’re nothing but a sidekick, man—a fucking clown. I’ve seen Chris leave behind a hundred of you. You’re an unpainted fucking clown.”

“Outside,” Donna said.

“What, Donna—you’re kicking me out?”

Donna had taken a few steps back against the mirror. She was pointing at the door.

“Yes,” Donna said. “Out. Go. Now.”

A half hour later Art came out with Hippy’s walking stick and some pizza. I’d made a big fire in the pit by the pond and was drinking a Beck’s from Art’s van. He set the pizza box on a rock by the fire. Handed me the stick. “Hippy wants you to have it for your limp.” Art sat beside me on the log. I handed him a beer. We looked into the fire for a long time together. Lights came on at Diane’s. Somewhere nearby Hippy’s dog had been buried. A starless night. The fire kept changing.

“Where are we unloading that lumber, Art?”

“Your therapist’s house.”

“I knew it,” I said.

“Is that going to be a problem?”

“No. It’s alright. Maybe I’ll make an appointment.”

“That’s probably a good idea.” Art opened the beer with his knife. “She wants a new deck.”

“That’s good,” I said.

“Lumbersweeney thinks you’ve cracked up.”

“Who cares,” I said. “Everything I said I could have said about myself. I wasn’t even really talking to him.”

Art laughed. Shook his head.

“I think I’m in love with Alma, man,” I said.

Art looked out into the night. I could hear Diane’s son screaming, playing, laughing.

“I don’t get what you’re so hung up about,” Art said. “That’s supposed to be a good thing, love.”

“I’m afraid Chris will never talk to me again. That’s best case scenario. Worst case scenario is—”

“They say when you bury a feeling you bury it alive, Sunshine. The same is true for love. You can’t decide who you love.”

“Sure you can,” I said.

“Well then do it already. Make your decision. Fear is stupid. You need to live your life.”

Art led us back up the hill through the dark. I liked the feel of Hippy’s walking stick in my hand. At Diane’s we unloaded the lumber loudly, board after board, thunk thunk thunk. Lights were strung from tree to tree and every window in the house was lit. But nobody came out. I tried to eat a slice of pizza but got the red sauce everywhere.

Art drove us back to the barn.

There were lights on in the farmhouse too.

“Wow,” I said. “Alma’s back.”

The van engine clicked as it cooled.

My Volvo looked like a coffin of itself in the dark.

“What’s this,” Art said.

I had tossed the birthday card onto Art’s yellow lumberyard papers.

“From Chris. It’s Saint Francis receiving the stigmata.”

Art leaned in closer to look, frowning, then he sank back into the driver’s seat.

“A stigmata is when—”

“No, no—I know about that,” Art said. “I thought you said stomata.”

Art got out of the van. I did too. The sky had cleared. The stars were out. It never did rain.

Alma’s body brightened the frame as she moved to and fro through her kitchen.

“You going over there tonight?” Art asked. “She still doesn’t have any water.”

“I’m too drunk,” I said.

Something hit hard against the hood of Art’s van with a thwack. We both jumped in the dark.

“It’s flowers,” I said. “Alma’s catalpa must be blooming too.”

“I know. I keep thinking I stepped in dog shit whenever I cross the road.”

I started for the hill with the help of Hippy’s walking stick.

“One thing before you hike up,” Art said. “My brother’s kid. Down in Arizona. Got into a little trouble.”

I had stopped in the middle of the street.

“I didn’t know you had a brother,” I said.

“I’m taking the kid in for the summer. Teaching ‘em how to work.”

“When?”

“Probably be here for the Fourth.”

“Jesus Christ. Okay. What’s his name?”

“Pretty strange kid,” Art said. “Name changes a lot. Right now they go by Spitgum.”

“Spitgum.”

“That’s right.”

“Alright, Art.”

“Nighty night, Sunshine.”

“Alright, Art. Goodnight.”

Dylan Smith is looking for a job if anyone knows of any jobs in Brooklyn.