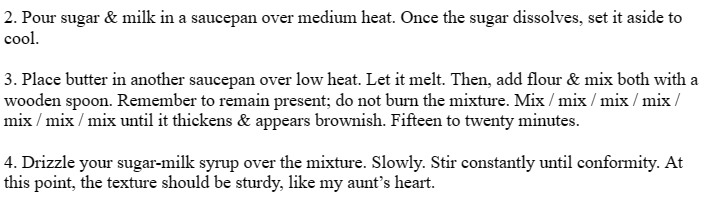

By Michael McSweeney

Burning past Buffalo through the wildfire haze, I wanted to feel momentous, part of a final history, a mover in the American age of malaise, a reporter in the heat of the breaking news belching from the Quebecois woods, spotlit by a low and violet sun. But in reality, I was alone, thirty-five, and afraid to die on the road to Chicago. Then a bald eagle flew through the window and landed beside me.

The eagle’s alabaster crown shone in the dying daylight. Feathers brown like melted chocolate. Its talons chewed the leather seat.

I waited for a lot of things to happen. All that happened was that I drove for seventeen more miles to the next rest area where I claimed a parking spot near the rear of the lot. When we stopped the eagle sang, a strident terrifying portamento. Its amber eyes tore me. Exposed my lowest, most degrading fears. Then quiet pooled inside the car.

I took a bag of jerky from the center console and peeled it open. Raised a chunk of salty beef. The eagle blinked at the jerky before seizing the meat with its beak. I watched its cruel efficiency and I chewed a piece of my own.

Peace lingered as we emptied the bag. The red sun squatted against unfamiliar hills. The dashboard blinked an eight chased by dueling zeroes. I took my phone from my pocket. Skimmed through a friend’s two-dozen unanswered texts. I wasn’t having a mid-life crisis. I was having a quarter-life crisis. I shouldn’t presume that I’ll die so young, they said.

I thought about answering. Then I dropped my phone in a cup holder and tugged the car into drive.

The eagle settled down after a few miles. I tried not to wonder about the costs of leather repair. It’s not every day a bald eagle catches a ride with you. I grazed the radio. The eagle flared at stations for techno, country, and bitter talk radio. It relaxed to some jazz. Closed its eyes. Ornette Coleman bore us into Pennsylvania.

I wondered if the eagle cared where I was going. A reading in Chicago. The next night and the next. A throng of writers and musicians for the renegade fall of America.

Two hours later the car curled around the hotel’s rear. I looked at the eagle. I couldn’t leave the bird in the car. Streetlights betrayed the choking air. The hot summer night threatened its advantage if the AC died. The eagle raised its head, as if expectant of a plan.

I got out of the car, came around to the other side, and opened the door.

Out you go, little guy. The eagle stared at me. I briefly considered risking the onslaught that would follow any attempt to lift the eagle or otherwise urge it physically out of the car. I gave up, returned to my seat, and closed the door. Then the first mad etchings of an idea came to me.

Uh…wanna climb? I asked, then held my arm out.

The eagled cocked its head and stared.

Okay, that’s not gonna work, I said. Then I said, Okay, let’s try this.

I stiffened my body and stared ahead. After a few moments, the eagle rose on the seat. Its eyes never left me. But the eagle’s movements, the feather twitches, the talon tweaks stopped. The bird didn’t so much as blink.

Yeah, I said. Yeah! I said louder, and the eagle chirped and gripped the ruined leather seat. We understood each other, I thought.

I mimicked immobility again. Then, carefully, in painstaking centimeters, I took the eagle in my hands. Held it close. Got out of the car, scooped my backpack from the rear, then paced a line of slow and anxious steps toward the hotel doors. Across the road rumbled a tavern, its outline neon-red. A pack of smokers heaped extra mouthfuls beneath a ragged awning. I kept walking and entered the cool touch of the conditioned lobby. The eagle made a soft noise but remained inert.

Cool bird, said the front-desk guy.

Thanks, I said, reaching for my wallet with my free arm. Never leave home without it.

Who did the work?

Eh?

The restoration. It’s really good quality, said the guy, and he leaned forward. I turned my body, to prevent a closer look.

Oh, uh, I’m not sure. My dad gave it to me. Found it in a dumpster. Really lucky find.

Pretty clean for something you found in a dumpster.

Don’t I know it, I said.

Our conversation waned as the guy chose my room. Two beds in the far corner. The pulse of fireworks broke through the walls and the eagle stirred in my arm. I cleared my throat.

Party outside? I asked, raising my voice.

That bar across the way, said the guy. Fucking maniacs. Fourth of July every night this week. I call the police but they do nothing.

That’s too bad.

I feel like a loser. Getting upset. But you get used to the quiet.

I know what you mean.

The vulnerable moment, the weakness the guy betrayed, slipped into nothing. He handed me two keycards and pointed me to the elevators. Once the doors shut the eagle stirred. Talons tested the bounds of my flesh. I shuddered under the immensity of its strength, restrained, watchful. We rose through the bones of the hotel.

Once in my hotel room, the eagle detached and drifted across the room to the bed. Plucked and tore at the sheets. I cried out and approached and the eagle snapped its beak at me. As if to say, I’m in control now. The eagle continued to tear at the bed. Like the wet heart of prey lay inside the sheets. I imagined dollars pouring from sliced arteries, dropped my things by the door, and went into the bathroom.

The mirror wouldn’t reveal whether the smoke had aged me. I flashed my teeth and remembered I forgot to buy toothpaste. Another misstep on the road. I searched beneath the sink and found the dead worm curl of a toothpaste tube. I squeezed it for signs of life. A tear of white squirted out. I rubbed it against my teeth, around my gums, the dry scrape of pharmaceutical mint. Then I stripped my clothes and stepped in the shower.

The eagle stood perched on the TV when I left the bathroom. One of its claws punctured the dark screen. The eagle twisted its head and watched me pull clothes on my still-wet body. I felt like prey. A cold and hollow wash. I imagine this is how the rabbit feels when it first spots a shadow circling on the grass.

I decided to go to the bar. I finished dressing, pulled on my shoes, and grabbed my phone from the bedside table. More texts from the friend. Don’t let that breakup fuck with your head. This isn’t the crisis you think it is. Call me. Call me. Ignore the anxiety. Happy 4th of July if I don’t hear from you.

I made for the door. A scuffle of talons followed close. The eagle, head tilted in seeming curiosity, croaked at me, as if wantingly. I extended my arm and the eagle climbed my leg and settled on the offered perch.

Alright then. I guess we’re gonna go drink, I told the eagle.

We left the hotel and traversed the toxic-mouthful paces to the bar. Patriotic glam rock slammed against us when we entered the sweat-breath swell of people. It made no sense how busy the place was, here on some highway-flung tavern an inch on the map from Lake Erie. I pushed closer to the bar. The eagle chirped and tucked its head close to my shoulder.

I tried to buy a whiskey sour and the bartender, a middle-aged woman with gray hair tied up in a knot, put her hands on the counter and leaned forward.

Is that a real bird or what?

As I started to stammer in reply the eagle raised its head to the bartender. Before the bartender could react, some drunk guy to my left leaned forward and shouted, Hey, this asshole’s got an America bird with him.

Eagle, someone else yelled. An American eagle. Or something.

America bird! the drunk guy repeated. Somebody get this America bird a drink.

The drunk guy tugged on my eagle-free shoulder.

Hey, buddy, let me buy your America bird a drink.

The drunk guy took some cash from his wallet and crumpled the bills on the counter.

Some beer for this America bird, he said to the bartender.

The bartender looked at me and then the eagle and then the drunk guy, and then his money. Picked up the cash, counted the bills, and then from behind the bar took a small wooden bowl and poured some beer in it from the tap. As she poured a crowd gathered around us, drink-brandishing gawkers sipping and watching and whispering about the eagle.

The bartender set the bowl on the counter and we all watched the eagle.

Go on, little fella, I said.

The eagle clambered down from my arm and rested on the counter. It lowered its beak to the bowl of beer, considered it, and then began to lap up the beer with its thin, pink tongue.

America bird’s drinking a fucking beer! the drunk guy shouted. The crowd clamored and cheered. The bartender poured my whiskey sour and I took a greedy swig. Then I bought the eagle another beer.

A woman in an American flag tank top pushed her way to the bar. She reached out and stroked the eagle’s feathers. The eagle kept drinking.

This is the greatest July 4th pre-game I’ve ever been to, she said to me. Then she asked, Is it safe for it to drink beer?

I have no idea, I said.

The bartender took her phone out of her pocket and typed. There’s a video on here about a crow that drank beer, she said.

She held the phone up to me. A grainy news clip from the 1970s showed a black crow hopping around a bar counter and sipping from mugs of beer. The crow knocked one of the mugs over and hopped around in the mess.

That’s amazing, the woman said.

We finished another round of drinks, and then another. I couldn’t remember the last time I’d gotten that drunk. I took my phone from my pocket and skimmed through the texts from my friend. It’s not like I wanted to ignore him. I just preferred to speed past my problems. Leave them in a ditch by the road. Drive until the accumulated damage blew the tires out.

The eagle jerked forward and snapped at my phone with its beak. It pierced the glass and I dropped the phone onto the counter. I reached for it, slowly. The screen still responded to my touch but now a crack-swirled puncture ruled its center. The eagle screeched. I released the phone again.

Trying to text someone important, the woman in the tank top said. The bar had grown louder so she had to yell to be heard.

Sort of, I said.

The bird is right. You should stay in the moment.

Maybe.

Don’t text at the bar. That’s a rule I have. It’s too easy to tell the truth and lie at the same time.

How does that work?

The woman thumbed her glass for a moment. I don’t know, she said. It just makes sense when I say it aloud.

I’m having a crisis, I told her.

How come?

It’s like, I don’t know why things are the way they are anymore.

Like what?

Like working. I work because I should work. And when I’m working, I worry about the next time I’ll work, and I worry if one day I won’t have work.

Like being laid off or some shit?

Yeah.

What about right now?

I don’t know. I guess I sort of forgot about it until I took my phone out.

Then keep that shit away. Live in the moment. Find hope in that. Hope in the moment.

The woman put her drink on the counter and laughed. Then she said, Maybe that’s hard to feel when we’re all choking on smoke. But it’s the truth.

Then someone dropped their glass and the people in the crowd expelled a collective ohh, and the eagle did too, hunching and croaking with delight.

The drinks kept flowing. I told the bartender I’d known the eagle since childhood. Best friend growing up. The eagle leaped off the counter and soared across the crowd and everyone cheered. Then the eagle flew back and landed on my shoulder. Talons tore through skin. I flinched but the whiskey dulled the pain. I was too happy to worry about anything.

The woman asked if I wanted to smoke. I said yes and she led me up a narrow staircase to the roof. I barely noticed the smoke in the air. Took an offered cigarette. After a few puffs, the eagle shifted and croaked again. I turned my head and the eagle was eyeing my cigarette. I held it up to the eagle. The eagle nipped at the end of it with its beak. Elation swelled inside me and I laughed.

Okay, I definitely think it’s bad for a bird to smoke, the woman said.

This eagle, I said. This fucking eagle.

You guys seem close.

He saved my life.

How?

Good luck. He’s a good luck bird.

Okay.

I wandered to the edge of the roof. The smoke in the air was still just as thick but I noticed, for the first time, that I could still see the vague etchings of light cast by cars on the highway. Speeding through the danger. Swiftly seeking home. The hint of forest stretched on forever. That’s beautiful, I said. Look at this night. Beautiful.

Be careful over there, the woman called.

I didn’t reply but I raised my hand to gesture with my cigarette. As if trying to wave my thoughts into focus. Invincibility, connection, America. I knew I had to do something to mark the moment.

Let’s go for a flight, I told the eagle. Just a little flap around.

There was no doubt that the eagle supported me. Believed in my ability to fly. We’d come too far together. The moment demanded we be airborne. I raised my arms and stepped beyond the edge. I remember the tumble, a shout from behind, the spin of my body, a harsh yelp, a furious flutter, a hot wet crack in my arm, the pavement, a swift and concrete unconsciousness.

***

I woke up in my car. Sprawled in the back seat. My left arm, stiff and swollen, was bound in a sling made from a bartender’s apron. My lungs ached. Everything ached. I sat up. Someone, the hotel staff probably, had collected my bags and left them half-open in the front seat. No note. Just a swift and silent ejection.

The world was clear through the smudged windows. The smoke drifted elsewhere in the night. I saw chipped-face commercial buildings with big garage doors like brown teeth.

After a stretch of wounded time, I moved to the driver’s seat and groped around for my belongings. No cash in the wallet. Keys under the floor mat. I clicked my phone’s broken screen and squinted at the time. 3 p.m. Half the day, gone. I should’ve been on the outskirts of Illinois by now. But there I was, injured near Lake Erie, wondering where the eagle had gone.

All I had were the remnants of the eagle’s presence. The fucked-up car seats. Scabbed-over cuts on my arms. The beak-broken phone. Stray feathers on the dash. Signs, but not proof, of a profound and wondrous experience. I wished the eagle hadn’t left. But maybe that was the point. The eagle was always going to leave. People experience miracles until they don’t. Nations fail because their people stop believing that temporary miracles are enough.

I started the car. The gas needle flicked up to the halfway point. Not enough to reach Chicago. Not enough to flee back home. No digital map to guide me.

But I had a destination, a westerly point, a daytime star. Skies clear for the first time in days. I’d survived a fall. I hadn’t died on the road to Chicago, not yet at least.

My body in revolt, I reached for the seatbelt.

Michael McSweeney is a writer from Massachusetts. He lives online @mpmcsweeney.