By Bill Whitten

Bergamaschi, a furniture mover who wrote books that sold modestly in France and Germany, stood by the open rear door of his illegally parked Mercedes LP Truck outside the Carlton Arms Hotel on E. 25th Street.

Aged thirty-nine, six-foot-one, one hundred-eighty five pounds he looked at his watch and sneezed. It was May and his body was in revolt. A Linden Tree was in full flower above him. He sneezed again.

A tall man in his forties with brown hair, wearing a grey three-piece suit approached him. “Well, that should do it.” The man was carrying a black briefcase in his left hand and pulled a wheeled navy suitcase with his right. He stopped, lifted a hand – covered in smudges of blue ink – above his brow to shield his eyes from the sun. “Do I pay you now or upon completion of the job?”

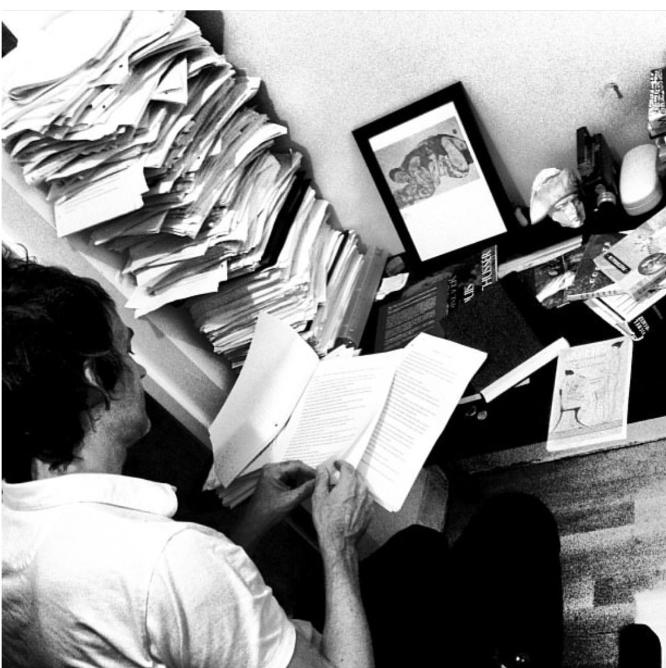

Bergamaschi picked up the suitcase, threw it in the back of the truck and pulled down the roll-up door. More than a dozen legal file boxes were stacked and strapped against the truck’s back wall. Each box was stenciled in white letters: J.MURK CONFIDENTIAL. He placed a padlock over the handle. “When we’re done.”

“Can I ride with you? Or does that violate a law of some kind?”

“You can ride with me, Johann.” Bergamaschi smiled and pointed at Johann’s shoes: “Watch your step getting in. It might be tricky in those Bruno Magli’s…”

On Park Avenue South, as Bergamaschi navigated his truck among the yellow cabs and bike messengers, Johann began to weep.

“Should I pull over?”

Exhausted, dislocated, breath rattling in his throat: “No, no I’m fine. It’s just that today is my wedding anniversary and my wife served me divorce papers…” His baritone tremoloed, his chest heaved, “…only yesterday.”

“I’m sorry to hear that…”

“My work, as my wife sees it – I’m a clinical psychiatrist – has destroyed not only my own life but hers as well. Columbia is currently attempting to fire me. I’m a tenured professor so lucky for me that will be nearly impossible. But they are discrediting me and she believes that due to the phenomenon known as guilt by association, her standing as a top-tier mathematician has been called into question.” He wiped tears from his cheeks with a monogrammed handkerchief. “It all has to do with a book I wrote – Interventions and Abductions – that has become a best-seller. ”

Bergamaschi slammed on the brakes as a UPS truck careened across the lanes in front of him. “What is the work you’re doing? What is the book about?”

Johann nodded his head as he pocketed the handkerchief. “I’ve spent the last decade interviewing and writing about the victims, or should I say, experiencers of alien abduction. This field of interest has possessed me. It feels as though I have no choice in the matter, as if I’ve been called to do this work.”

Bergamaschi looked past Murk at the side-view mirror on the passenger side of the truck as he attempted to change lanes. “You might think this is strange, but there is someone I know – an experiencer as you say – who might benefit from talking to you, if you’re interested and not too busy.”

Murk closed his eyes, leaned back against the seat and took a deep breath. “I think it goes without saying that I’d be very interested.”

***

The two men sat at a table in Leshko’s on Avenue A. They stared out of its dirty windows as they waited for their coffees to arrive. A woman with tears streaming down her face, a nameless rapture in her eyes, paced back and forth on the sidewalk. She was followed by a man with a shaved head, dressed in black clasping a small white Chihuahua to his chest. There were dark circles beneath the man’s eyes and tearstains beneath the Chihuahua’s. Occasionally, the world revealed a strange, undeniable consonance.

“The young man I’d like you to talk to is a painter. I met him through his girlfriend who lives in the apartment building next to mine.”

A waitress appeared. Young, blonde, Polish: “Your coffee gentlemen.”

Bergamaschi smiled: “Thank you Zuzanna.” He paused, lifted the cup, blew on the coffee. “He was scheduled to have a show at a gallery on West Broadway. Not a top gallery by any means, but his paintings would have received quite a bit of attention. At the last moment he backed out and then…like in some melodramatic movie from the 1950s…burnt all the paintings.”

Johann’s was a handsome, pockmarked, olive-skinned face. On some men, acne scars are almost a kind of decoration. Think of a statue pitted by time or disaster. Johann was one of these men. He stirred milk into his coffee, raised his eyebrows. “But why?”

“He claims that the subjects of his paintings were directly the result of…how do I put this…alien intervention. According to his girlfriend he claimed the aliens have been visiting him since his childhood. In the course of their interaction the aliens have shown him things; images from a vast archive that is essentially the history of human civilization. He’s seen the Crucifixion, the Wright Brothers at Kitty Hawk, the construction of Ai Kanoun as well as the Great Pyramids, the Battle of Somme, the beheading of Robespierre…an endless list of events and occurrences that were, according to him, imprinted directly onto his mind. These events became the subjects of his paintings…Even the idea of painting itself was suggested to him by the…the…aliens.”

Johann could not take his eyes off the man with the Chihuahua: “Most of the experiencers that I encounter feel that an urgent message about the fate of humanity has been delivered to them and it must be communicated to the rest of the word…before it’s too late.”

Bergamaschi nodded, sipped his coffee. “Prior to moving to New York from Missouri, he was a landscaper, a housepainter. He was fired from a job after he painted an image of an extra-terrestrial on someone’s garage door. He hitchhiked here, met the young woman I mentioned who encouraged him to paint. His paintings are – or were – like a crazy combination of Basquiat and Henri Rousseau. One gets the impression that this young man is being propelled through life by a force outside of himself. His girlfriend fears that something terrible is going to happen.”

“More terrible than the burning of his paintings?”

“Yes. Perhaps I could bring you to meet him? He doesn’t like the City and has moved to a town called West Stovefield, about an hour north of here.”

Johann had shifted his gaze from the man with the Chihuahua to the woman with tears streaming down her face. “The apartment you just moved me into is almost completely empty. There is one coffee cup in the cupboard, one can of Budweiser in the refrigerator. My only plans are to read the Zibaldone alone on my futon at night. Arrange for me to meet your friend. The sooner I get back to work, the better.”

***

The two men exited the Taconic State Parkway in Bergamaschi’s beige D-100 pick-up and approached West Stovefield along the narrow two lane Harvey Door Road as it wended its way along a tunnel-like corridor of birch, pine and elm. Occasionally, on the left or the right, the men saw in the perpetual sylvan twilight a grim looking double-wide rising from the earth. As often as not, a pick-up truck was parked nearby. Perhaps, somewhere on the adjoining property, a satellite dish pointed at the sky.

Mark Finger was staying in a rented farmhouse on the edge of West Stovefield near its northern border with Granville. Grey with white shutters, it rose above rutted, fallow fields, the only structure visible for miles. Finger’s blue Chevy pickup truck was parked beneath a towering Oak. From the tree’s silent, gray branches a frayed rope swung in the wind. Perhaps a tire once hung from the end of it.

Finger stood on the front porch as Bergamaschi steered the truck along the dirt driveway. He was in his mid-twenties. Dark hair swept back from his forehead. Beneath a black t-shirt, broad shoulders and a narrow waist were visible. Except for a discolored, cracked front tooth there was a symmetry to his face and body.

Through the open window of his truck Bergamaschi observed the rhapsodic blue of the sky, the vapor trail of a fighter jet, the rustle of leaves in the wind…

Finger ran down the steps, across the lawn and stood outside of the truck waiting for the men to get out. He was laughing. He pointed at Murk. “I know who you are. I have your book.”

Murk climbed out of the truck, shut the door to the pick-up, smiled and began to laugh as well.

Bergamaschi leaned against the door of his truck. “What’s so funny?”

Murk: “Certain essential aspects of the world are accessible only through laughter.”

Finger: “Sometimes fear is laughter.”

Murk: “To laughter you can only oppose laughter.”

Bergamaschi followed the two men as they walked toward the house. “My grandmother used to say: madmen are the salt of the earth.”

***

“I want them to leave me alone. I’ve had enough. I reject them.”

The three men sat at the kitchen table, drinking from cans of beer.

Murk drummed his fingers on the tabletop. “Of all the experiencers I’ve encountered, more than half of them have expressed the desire to be left alone. It’s the same with mystics or visionaries: exposure to another reality can be unbearable.”

Bergamaschi stood up from the table and pointed toward the kitchen window. “Look.”

A woman, barefoot in a white linen suit crossed the lawn. Her hair was black and gleaming, her skin ivory, her eyes like bodies of water reflecting the sky.

In her left hand, held between thumb and index finger, a paperback copy of Interventions and Abductions. As she walked, plants broke through earth and rose to attention. Their flowering was violent, the colors jarred like wrong notes played on a piano. She continued to walk, grass sprouting at her feet, fog rising in front, behind her.

She did not speak, but the three men heard her voice. “To survive you must transform the nature of all that exists and enter a completely new order of things. Debasement has been your fundamental principle of existence. The best painting, the best art is initiatory. It heralds a new world and helps bring it into being. We must guide you to a zone in which a new conception and a new birth can take place.”

The woman continued walking until she was no longer visible. Bergamaschi once again sat down at the table. In the instant that followed the men were without memories, without plans. An interval of unknown duration passed as time rebuilt itself around them.

Finally, Murk began to scribble in his notebook. He spoke in a hoarse voice: “There is a taxonomy of aliens; we know of the Greys, the Lizards, the Little Doctors and the ones like her called The Nordics. Sometimes they appear to our sensory organs as over seven feet tall.”

Finger was slumped in his chair. “They’re in the barn, they’re in the trees.” He gulped his beer. “You hear noises at night. You might think it was crickets or toads or birds but it’s them. They won’t leave until I start painting again. They’ve made that clear.” He stood and walked to the refrigerator, pulled open the door, retrieved another beer. He pointed his chin toward the kitchen door. “If I drink myself to death or blow my head off or burn this place down they’ll be shit out of luck.” He gulped half the beer, then paused. “But, that’s not what I want…I want to be…” He grimaced: “I want to be normal.”

Bergamaschi closed his dark eyes, rubbed a hand over the black stubble on his cheeks. “Why don’t you start painting again? I’d do anything to get rid of them…”

Johann closed his notebook. “Come with us when we go back to the City. I just moved into a large two-bedroom apartment that’s almost completely empty.”

Finger shrugged. He placed the empty can of beer on the table in front of him. “Let’s go shoot some guns. It’ll clear our heads, make us feel better.”

***

Murk put his right hand against the dashboard and braced himself as Finger jerked the wheel and steered his pick-up truck down a rutted dirt road.

They passed remnants of a shade tobacco field, then the charred skeleton of a tobacco-drying shed.

Like a sullen teenager Murk frowned and stared straight ahead. “I always promised myself that I would never fire a gun.”

“That’s pretty silly”. Finger turned and grinned. “Just a little farther now, Dr. Murk.”

The truck hit a rut and the three men’s heads nearly banged against its roof.

“Should we be firing guns after drinking alcohol?”

“It’s the best time to fire guns. The type of people I grew up with were always armed.” He lifted his hand from the steering wheel and tapped one of the rifles affixed to the gun rack. “These are tools; like a paintbrush or hammer.” He pulled up a pant leg. A derringer was visible in a boot holster.

Murk sighed. “We shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us.”

Finger laughed. “Whatever.”

Wedged against the passenger-side door, Bergamaschi was bored. “Why is that the aliens are so intent that you in particular, should paint?”

“You heard her. They want the world to know that our technology has enslaved us and compelled us to participate in our own destruction.”

“But why you?”

Finger turned toward Bergamaschi and shrugged. “No clue. I have a feeling it’s just their cover story. They’re after something else. Doc Murk might know what that is.” He patted Murk on the back. “Stop shaking, I’m about to put a loaded gun in your hands.”

Up ahead, like a beaver’s dam, a small mountain of brush blocked the road.

“Here we go, gentlemen.”

Finger stepped out of the truck, shut the door, leaned against it and pulled a pack of cigarettes out of the pocket of his t-shirt. The sky was darkening. The holiday feel of an impending thunderstorm penetrated the air. He took off running. Thirty yards away from the truck he went about setting up a dozen empty, green Genesee Cream Ale cans. He jogged back to the truck, opened a door, removed the two rifles from the gun-rack and laid them on the hood of the truck. He pulled a gym-bag from behind the driver’s seat, removed a loaded magazine, popped it into an M-1 and handed it to Bergamaschi.

“Patty Hearst’s favorite weapon, give it a try Mr. Bergamaschi.”

As Finger and Murk stepped aside Bergamaschi put it to his shoulder. Bergamaschi pulled the trigger. There was no evidence of the .30 caliber bullet striking anything near the row of cans. He lowered the weapon, rolled his shoulders and once again took aim. As he did he recited:

“Where there are no gods, the phantoms reign.”

He began firing. One after another, cans flew from the log as if pulled by a string.

***

An enormously tall, thin blonde-haired figure wearing a white tunic-like garment and fluorescent orange running shoes wandered in the distance, slightly to the right of where Finger had placed the targets.

Finger held a .44 Magnum at arms length. The gun discharged. Beer bottles exploded in the distance. “That’s Zaoos; he hardly ever shows his face.”

Bergamschi sat on the truck’s tailgate drinking a beer. “What happens if you shoot him?”

“I’m pretty sure he dies.”

“Why don’t they intervene directly; cure disease, stop the aging process, disarm the nuclear bombs, clean up the polluted oceans etc etc etc.”

Murk held a beer in each hand and drank first from one, then the other. “As Mark has said, they may in fact have other goals aside from our salvation. Some insist that their only interest is in maintaining themselves. Their true work is to use humans to propagate their own species with what have been called ‘hybrids’.”

Finger snorted and fired the Magnum.

Murk emptied a beer can, then crushed it in his fist. “When they first started visiting you did bright lights appear outside your window? Accompanied by a strange hum?”

“Yep.”

“Did they de-materialize you?”

“Yep.”

“Did they then transport you through walls or windows?”

“Windows”.

“Did they take you to a mother-ship with gleaming modern appurtenances or a room that seemed like an ancient shrine or altar?”

“Ancient shrine.”

“Did they perform medical interventions?”

“Yep.”

“Harvest your sperm or take tissue samples?”

“Sperm.”

“Did their ship, as far as you understood, come from the stars or the oceans?”

“Oceans.”

Lightning flashed, claps of thunder quickly followed. A bit like a priest, a bit like a ballerina Zaoos wandered in the distance. His voice cleared a space in their brains: “What we seek is neither thick nor thin, neither short nor long, neither flame nor liquid, neither colored nor dark, neither wind nor ether, doesn’t stick, is without taste, without smell, without eyes, without ears, without breath, without mouth, without measure, without an inside, without an outside. It does not eat and is not eaten.”

Murk, holding his head in his hands, ran back to the truck. “We are not able to endure these creatures. Like Semele we’ll go up in a puff of smoke! I have a splitting headache! Let’s go! Back to the farmhouse and then the City. Please! My head!”

***

Upon returning to Manhattan, both Bergamaschi and Murk were bedridden for a week with headaches and fevers. Finger, on the other hand, was afflicted by a kind of hyper-restlessness; he did not sleep and drank around the clock. He stayed with Murk for three weeks, then his girlfriend (who, after the burning of the paintings and the end of his art-career had become his ex-girlfriend) for two weeks, then with Bergamaschi for ten days. After that, he disappeared. For weeks following his departure, Bergamaschi dreamt of him. He thought often of Finger’s pathetic even poignant desire, which was both commonplace and exceptional in a city like New York: I want to be normal.

The dreams usually ended with a vision of a vast conflagration. One morning upon waking Bergamaschi wrote down the details of his dream in the notebook he kept by his bed:

The house burnt, in the middle of all that empty space, like a torch. Windows popped, exploding outward, broken glass tinkling like ice-cubes on the frozen lawn. It seemed as if the house had been designed for only one purpose: to burn dramatically on a summer night beneath a sky full of stars.

The old Oak went up along with the house. The rope acted as a wick and the tree, illumined by orange-red flames, bent in the wind as if it was dancing.

A flaming branch fell on the hood of the truck. Then another. Soot rained down from the sky, plasma-like flame crawled upward from the windows, searching among the eaves…

***

Bill Whitten is a musician and writer. He is the founding member of St. Johnny, Grand Mal and currently records under the nom de guerre William Carlos Whitten. His latest album Ecstatic Laments was released in June 2022. His book BRUTES, a collection of short fiction was released in January 2022.