By Craig Rodgers

Craig Rodgers is the author of ten books, a handful of lies, and all manner of foolishness.

By Craig Rodgers

Craig Rodgers is the author of ten books, a handful of lies, and all manner of foolishness.

Sofija Popovska just doesn’t know anymore.

IG: _aughtmilk

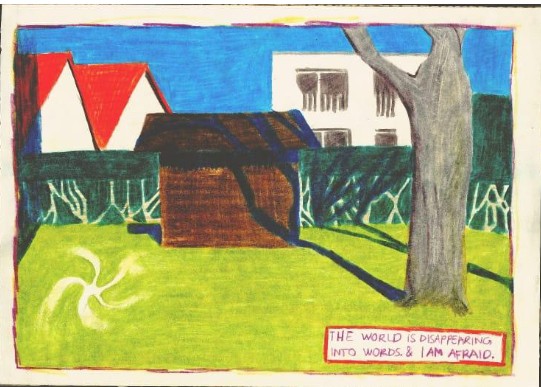

By William Schaff

William Schaff has been a working artist for over two decades. Known primarily for his mastery at album artwork, (Okkervil River, Godspeed You! Black Emperor, Mighty Mighty Bosstones, Songs: Ohia, etc.) Schaff is also the founder of Warren Rhode Island’s “Fort Foreclosure”. The building, lovingly named without the least bit of irony, serves as Schaff’s home and studio as well as home and meeting place for other artists (most notably former resident musicians MorganEve Swain, and the Late David Lamb, both of Brown Bird). William also performed for a decade with the What Cheer? Brigade, as one of 20 musicians in a brass band that travelled the U.S. and Europe. An experience that shaped so much of his life. In 2015, recognizing the importance of art in this world, he expanded his community to the West Coast, where he started “The Outpost”, in Oakland, California. There — financial earnings be damned! — William filled his days creating works of art for private commissions, bands, exhibitions and his own examinations of human interaction. He has since returned to Rhode Island and can be found, daily, doing the same at the Fort. He has a Patreon page if you’d like gifts in the mail and to help keep the lights on.

By Frank Carellini

they undressed methodologically. unprovocative. like they were about to examine each other for lumps. folding his clothes neatly into rectangles. those worn brown chinos. the chambray button down shirt with underarms that smelled with years of his bitter sweat. sweat that at one time, attracted her. she used to liken it to “my salty Mediterranean man that smells like the rind of a lime.” where that man went, neither of them knew. the fauvist views of succulent fruits clinging to branches above a sparkling sea are a lifetime removed. she, folding her jumper into a square that ballooned at the edges. never had a penchant for perfection. their bodies were cold and clammy as they came into mutual embrace. they tried to make love. tried pressing the atoms of their bodies into some form of miracle. paused at each others lips, not moving, but waiting for some sort of momentum to build. nothing. barely air passed between them. they tried in the kitchen. in the bathroom. on the couch. looking around at the set of japanese steak knives, the Breville, a distressed velvet ottoman. as if to put the blame on them for lack of ambiance.

checking into The Schofield. Corner suite (always wondered what it looked like). Lots of mirrored surfaces. their bodies moved like lava in a lavalamp from one distorting surface to another. two beds. weird, he forgot to request one king. lots of vague objects. a miniature Calder mimic. she put pressure on one pendant. let it ricochet. watched it ease back into balance. then into stillness. the lack of its optionality into a chaotic form was upsetting. couldn’t be broken. he went into the mini-fridge. two bottles of tonic. little bottle of bombay. grabbed glasses from the desk. they had a nice weight. a weight that felt official. called for ice. and a lime. two thank yous and a $10 tip later, he mixed them a drink. thumb stung from the lime juice. she was sitting on the edge of her bed. patting her skirt. she wore that perfume. he sat at the desk chair. swiveled around to cheers her.

“i used to wear a beret.”

“and smoke cigarettes.”

“i once knew Yves Klein. he asked me to be one of his brushes.”

this went on. the days in montmartre. maybe it was true. he was no Yves Klein. he could see it. her body draped in that ultramarine. being spread across a canvas. the gushing figures materializing on canvas.

this aroused, then irked him. didn’t dr. muchlenbach teach her not to bring french painters to romantic getaways.

he downed his drink. she hadn’t touched hers. the ice had melted and it looked diluted. he went and sat on the bed opposite hers. turned the tv on. Joe Rogan’s Fear Factor, Couples Editions. the programming at this place was meant to keep things spicy. she sighed and got up off the bed, placing the drink down on the desk. walked by him without any acknowledgement. he heard the bath turn on. ran for a while. this episode, contestants had to stand on top of a moving vehicle and grab flags as they sped by a set of markers. she, in a bathing suit (why were they always in bathing suits) and he, a muscle shirt, cutoff jean shorts. after they win first place, they’d go back to their trailer and have mind-blowing sex. maybe the exercise the entire kama sutra. this irked, then aroused him. annoyed at the thought of an erection through jean shorts. felt like an insult. the faucets turned off with that creak that the old guard turnstile knobs made. he could hear her swishing around. sitting up. falling into the water. now she was rolling onto her stomach and back. now she was—

the second task was a water one. one of the team would be submerged underwater. the other would have to crawl through a tunnel of roaches to find a key. the key opened the tank and let the water out. jean shorts muscled through the tunnel. even ate a roach for style points. bathing suit floated glamorously in the tank. did a twirl to the right, then to the left, then winked at joe. then to the camera.

drive home was eventless. across the bridge. down the parkway. Nicholas greeted them at the door. Said something about the dogs behaving well. they sat on the couch. he turned on the tv. maria appeared from the linen closet with a “miss, the blue does not come out of your underwear.” she blushed.

“I used to wear berets.” she uttered. “and smoke cigarettes.” she was speaking to a void. he went to the refrigerator. took two bottles of tonic. he put ice into his. lime into hers.

Frank Carellini was born in Connecticut in 1993.

By Craig Rodgers

Craig Rodgers is the author of ten books, a handful of lies, and all manner of foolishness.

By Kyle Kouri

Yves is dating Alfonse who’s in love with Paulo who’s fucking Stefan who’s focused on his career but married to Sydney who knows he’s gay but feels safe because they’re best friends, which makes Cristof jealous because he’s pining for both of them; and Cristof’s brother Rosco is dating Nifath, mysterious Nifath, and they’ve been in an open relationship since July when Nifath got distant and Rosco suggested they experiment; but Nifath’s been fucking Conroy since May of last year and Conroy hasn’t been tested for decades (no self-reflection); he’s been drinking with Jason who can’t get his dick hard but has been thinking it’s because he has feelings for Seana, the trans girl, who dated Sarah all throughout undergrad; and Sarah, stubborn Sarah, feels cheated because Seana’s not Sean anymore, in fact she’s never been, just appeared that way, and Sarah’s straight and sure of it, but did have a few experiences with Massie, the Bohemian, who swears relationships are soul-suckers, monogamy equals weakness; though in high school Massie dated Scottie, who is a cheater with a big ol’ penis, and has never once been loyal, but is charming, and still supported by his mother, who’s having an affair with Aldo, her personal trainer who does this frequently; and Aldo’s brother Santo is in prison and having a hard time while doing hard time because his girlfriend Mary is pregnant and works at the ShopRite which Peter has managed for sixteen years; and Peter, peculiar Peter, has had physical contact with another human only once during his entire adult life, instead he looks at little kids on the dark web; and sometimes, around lunchtime, he’ll make a detour carrying his canned tuna and pass by the elementary school’s playground where Fanny, Ms. Fanny Appleton, is the teacher and always gazes warily around the perimeter, because she’s worried about just this kind of thing; she purses her lips, eyes vigilant, and waves at Peter but doesn’t suspect him, because at the ShopRite he’s always been a nice man, a little sweaty, true, but even makes Ms. Appleton’s nephew laugh; this kid’s name is Stephen, and when Fanny’s babysitting, they stop by the store for ice cream sandwiches, but she has never noticed Peter touch him inappropriately, which, on one occasion, Peter has; anyway Ms. Appleton is single, has not had a boyfriend since college, where she was manipulated by Michael into doing things that didn’t feel right; and then one night Michael snuck into her dorm room, wasted, and raped her; now Fanny trusts no one and lives a quiet life but has a crush on Lucien Carr (no relation to the murderer), who teaches English and seems in Fanny’s opinion sweet but sad too, and everyday she swears she’s going to ask him out for coffee, but just hasn’t committed yet; and Lucien doesn’t realize she’s even interested, because the truth is he has a drug problem, and every day after his class he goes home alone, draws the blinds, snorts cocaine and drinks alcohol until he’s completely deranged, then sleeps for two hours, wakes up the next day, and repeats the same thing; sometimes he picks up his phone to call Courtney, then changes his mind, because Courtney was his wife and his best friend but then got sober, they both went through the Program, and she changed, he couldn’t beat it, so she left him, and now he’s back on a bender; and Courtney, somber Courtney, sweet, sad Courtney goes to meetings every evening and spends her days working at T-Mobile, just trying to get by; on occasion she flirts with Teshawn, her co-worker, he makes her laugh, they take break at Chipotle; Teshawn’s twenty-one and goes to the community college with Rasheeda, who he’s in love with, and she likes him, but he’s so nice, she finds that off-putting; plus she likes to go out on the weekends, in the city, where she meets Sky Pepper; and Sky Pepper, so Sky Pepper, is a model and comes from money and once her and Rasheeda went home with Sven Odenfield, the photographer, and they had a threesome, which was fun but a little intense for Rasheeda, though Sky doesn’t remember it; Sven remembers it, in fact he catalogued each moment of the evening in his Moleskine, because that’s his thing, along with photography, he’s in love with pleasure, has fucked half the city, and meticulously records each conquest; but Sven, complex Odenfield, still Facebook stalks Nadia, his step-sister, who lives in Berlin and will not return his phone calls, plus things were never the same after what happened that one night, when they shared a hotel room next to their parents and both got drunk off the liquor in the mini-bar; and their parents are swingers, they go to the private parties that Thor hosts; and Thor is from the midwest but got outta there the day he turned eighteen, and lives glamorously, hosting orgies, with celebrities, but has a soft spot for his sister Irene, who moved to New York, but couldn’t make it and so moved back home and married Alan, her high school sweetheart, who’s perfectly content in Wisconsin, he’s an engineer, would never leave there, couldn’t imagine life outside of Waukesha; and now Irene’s pregnant, she’s only twenty-five, and Alan is overjoyed (also in debt) and Irene is happy, she has always wanted to be a mother, but she wanted a career too, that’s why she moved to New York, but now it seems that ship has sailed; so once a week Irene FaceTimes her best friend Meredith, who moved to LA, and isn’t sure exactly if she’s the only one but is pretty sure she’s now dating Smash Lowe, yes, that one, the movie star, and is having so much fun and, “No, no, Irene, I do not have a coke problem, I don’t do it during the week, okay? Anyway I’m young! And Oh Irene, oh my god, you’re so freakin’ preggers!!!” and Meredith is having a great time, really living life, posts often on Instagram, but she’s secretly jealous, because throughout childhood she was in love with Alan too; her, Irene and him were inseparable, sometimes they all slept in the same bed, and Meredith once even, just once, after they’d been drinking, tried to kiss Alan but he was honest, he was loyal, he said, “Gee, Mer…I….I’m with Irene!” and was truly baffled, simple Alan, he was embarrassed, felt his honor compromised, but Meredith sobered up, she said, “Of course, no, you’re right, I’m sorry, can we just forg”—and Alan interrupted her, stood up very straight and said, “Enough,” then went into another room of the party and spoke to Johnny who developed his alcoholism at a young age and now is dead after taking too many Lorazepam on a March night, after a long bout of drinking, a few years ago; and at Johnny’s funeral his mother Aubrey cried, and his father Alec held her, stoic, but his mouth twitched and he thought that later that night, he’d sit by the fire with Skaal, his brother, who just flew in from Norway; and Skaal used to be easygoing, believed in the essential good of things, was always smiling, didn’t watch indie movies, liked buddy comedies, but that was before the Norway massacre, which killed 77 people, one of which was Anita’s little brother (that’s Skaal’s girlfriend); I shall not say her brother’s name, respect for the family, understand, but after the murder Anita became focused, she became political; Skaal, in contrast, became quieter, more sensitive, had less conviction, the world made less sense to him, and so when Alec called about his son’s death, Skaal’s nephew, Skaal blinked twice, held the phone and felt utter numbness; that trance persisted the entire flight to Chicago and still at the airport; and walking through the long terminal, dazed, startled by ascending airplanes, Skaal accidently bumped right into Olivia; and Olivia, who was about to board her own flight, took this as a sign; she turned around, left the airport, and caught a taxi back into the city, and ran to Henry, he was just stepping out of his apartment, she embraced him, and Henry was shocked, he thought he would never see her again, and he held her, but was anxious, frankly part of him had been excited for his new life, and thus was not expecting this return; and one night a month later, Henry got a little drunk and struck up a conversation with a woman at the bar near his office, she was wearing a black slip, her name was Terry; and Terry knew his type, she did this often, she got him wasted and then she fucked him, then kicked him out of her apartment and smoked cigarettes, thinking men are idiots, they are malleable, they are so easy; and Terry was the hostess at a very upscale restaurant on the Northside; and one night the famous musician and notorious womanizer Augie Rainwell came to the restaurant and ignored Terry, he did not seem interested, she was astonished; the fact was, however, that for Augie it was nothing personal, he was secretly dealing with an eruption of genital herpes, and that was affecting his confidence, he looked around the restaurant warily, helplessly, thinking everybody knew his deformity, everybody was doubting his masculinity, his sexual viability; he had no idea who had given him herpes, there were about seven women and two men that it could have been; and what was worse, the worst part of it, was that Augie was married to Jaclyn, and he had slept with her twice, without protection, since fucking strangers, without protection, and so now it was possible, perhaps likely (who knows how it really works), that Jaclyn also had genital herpes and would, once and for all, know that Augie was cheating on her; and Jaclyn, fed-up Jaclyn, would finally move out and go stay with her mother; and her mother, Avi, in the living room, would say, “I knew that boy was no good for you,” and Jaclyn would say, “Oh mother, please!” and turn away, look at their wall of photographs, where her grandmother Maya is featured prominently; and Maya was a Holocaust survivor whose husband Ira didn’t make it, but whose best friend David made it; and after the Holocaust, David wrote a book about the horror, but it was never published, and so he became a businessman, was quite successful, he married and lived a long life, ending up in a lovely home where he had a nice relationship with the nurse Genevieve, who is a redhead; and Genevieve loves to fuck, but has this feeling, this deep-rooted conviction, that abstinence is the only true path to happiness, but if that is the case she prefers unhappiness, and so has many lovers, and many secrets; and each one of these lovers say the same thing: “Genevieve was, by far, the best I ever had, but honestly, to this day, I know nothing about her;” and one of these lovers was Elliot, and Elliot has had a strange life; not only did both his parents die on 9/11 (one of those freak things, they were just visiting), he also happened to be in one square mile of two mass shootings in real life (one Isis-related, the other a white kid, with a micro-penis and a manifesto); but Elliot is committed to mathematics, he refuses to become superstitious, and right now is in grad school, getting his PHD; and Elliot, ponderous Elliot, the orphan prodigy, has never been in a relationship that lasted more than six months, they’re not practical, plus he cherishes his alone time, takes long walks, and thinks about probability, possibility, the infinite number of things that could happen to you, the infinite ways in which they could happen too, and the ways that lives intersect and influence each other, or maybe never cross paths at all, he thinks about all of this; and one day Elliot passed a family on one of his long walks; it was a mother, father, and their young boy; and that little boy was me, many years ago, my family lived around the corner, in that neighborhood, this was our park, it was small, now I see that, but back then it was the world to me; I held my mother’s hand and looked up at my dad’s body, obscured by sunlight, a vague shape, this awesome bulkiness, I tried to grab his leg, but he was too far ahead, didn’t even notice I wanted him; not at all; my father was focused on a sculpture, in the garden; this sculpture was a rabbit with big and ugly, rotting buck teeth, it wore a top hat and a sports coat, it held a watch in one paw and between two fingers on its other hand it balanced a scale, but unevenly; this rabbit smirked, taunting, mischievous, he knew everything, she was not impressed with it; they were sexless, gushing with sex though; I stared at my father and squeezed my mother, tighter, tighter, but then some smell, a floral fragrance, with the slightest rot in it, made me look away; I saw a man with long hair, very thin, very feminine, his shirt was see-through, rib showing, he was almost glowing; getting closer to us; he was not my parents, this excited me, my eyes opened, I tore from the woman who gave birth to me and ran, past the man who fucked her, I ran, and almost tumbled, but stayed on my feet, I ran forward and reached for

Kyle Kouri is an award winning actor, writer, filmmaker, and producer. He received his MFA in Fiction from Columbia University, where he served as the online arts editor for the Columbia Journal. He is the co-founder of Slashtag Cinema, a film production company. Slashtag’s first film, the multi-award winning KEEP COMING BACK, which Kouri directed, co-wrote, and stars in, premiered at Screamfest in October 2024. His writing has appeared in Cleaver Magazine, the Columbia Journal, Ghostwatch Zine, The Los Angeles Press, and Maudlin House. His first book, THE PROBLEM DRINKER, is forthcoming from CLASH Books in 2026. He lives in and around LA with his four rescue dogs and his girlfriend, the writer CJ Leede.

By Alex Rost

We weren’t getting along too well just then, so we went bowling.

We walked in at the far end of the alley.

“I love how it smells in here,” I said.

You wrinkled your nose. “It smells like dirty socks and stale beer.”

“I know, right?”

It was a long way to where we had to pay and rent shoes – past rows of alleys, past bunches of people milling about, talking or not talking or whatever.

“No one is bowling,” I said.

“Yeah, what’s up with that?”

“Why isn’t anyone bowling?” I asked the employee after we covered the ten fucking miles to the register.

“League play,” he said. “Hasn’t started yet.”

“Oh,” I said. “That makes sense.”

Now I could feel it – anticipation. That was what really smelled.

The employee must have said something, because he was staring right at me.

“What?”

“It’s gonna be like twenty minutes. We only have the last ten lanes for open bowling tonight.”

“Only ten lanes?”

“Leagues,” he said, and pointed off behind me.

“Okay.”

“Or thirty.”

“Or thirty what?”

“Or thirty minutes. Twenty to thirty minutes.”

I turned to you. You shrugged and nodded at the same time.

“Okay,” I said to the employee. “Let’s do it.”

“How many games do you want to play?”

“Three. At least three, I think.”

I turned to you again. You shrugged and nodded at the same time.

“Three games,” I said to the employee, with confidence.

He typed something into the computer on top of the register.

I noticed an index-sized laminated card propped on the counter. It said, ‘Buy three games, get a $5 arcade play card.’ It said, ‘STATE OF THE ART ARCADE!!!!!’ with all those exclamation points.

“Hold up.” I flipped the card around and showed it to the employee. “What’s this all about?”

“You get a free play card with a purchase of three games,” he said.

“Both of us?”

“Yes, both of you.”

“Were you going to say anything? Like if I didn’t notice this, would you have given us the arcade cards?”

The employee raised his eyebrows.

“Is it really state of the art?”

He pursed his lips, glanced at the line behind us.

“I mean, is it worth it?”

“Are you going to buy three games?”

“Well, yeah.”

“Then I’d say it’s worth it.”

“Okay,” I said. “Done deal.”

I turned to you, grinning, and said, “State of the art, baby.”

You shrugged and nodded at the same time.

“What size shoe?” the employee asked us.

You told him your size and I said, “Sometimes a twelve, but sometimes a thirteen.”

He slapped a size twelve and a half onto the counter.

“Whoa, man. Twelve and a half? Thank you.”

We paid and headed to the bar. I held my shoes up, showing you the 12 ½ printed on the heel.

“I can’t believe they had a twelve and a half,” I said.

“I think it’s pretty standard.”

You didn’t understand.

“I feel like I should tip him.” I looked back at the employee. He was helping someone else now, looking sleepy and annoyed.

“He was kind of a dick.”

There was one bartender, busy filling a tall tube with a spout at the end full of beer.

“Check it out,” I said. “A hundred twenty ounces. That’s like a full twelve pack.”

“That’s ten beers,” you said.

“Sure is. Should we get one?”

“No way, that’s fucking gross.”

“Really? Why?”

“How do you think they clean those? Rinse them out with a hose? No way they’re sanitized.”

Maybe they had a sort of chimney sweep tool they jammed in the tube to scrub it, but I doubted it.

“You’re right,” I said.

“Plus, it’ll get all warm and flat before we drink it all.”

“You’re right,” I said again. “Fuck.”

We ordered beers – boring ass regular size beers – and took them to the arcade.

It’d been a while since I’d been in an arcade, and this one being billed as state of the art had me all excited.

“What the fuck?” I said when I saw it. I said it louder than I meant to.

“That guy said fuck,” said a little kid, walking past.

“I heard him,” said his little kid buddy.

The arcade had a bunch of claw machines in the middle, like an island, and your standard ticket winning games like basketball toss and whac-a-mole along the walls. The featured attractions were two ten-foot screens – one showing a giant version of Pacman, the other Asteroid.

We stood under the ten-foot Asteroid screen.

“State of the art?” I said. “You can’t take a forty-year-old game, put it on a big ass screen, and call it state of the art.”

“So you don’t want to play it?”

“God no.”

We picked the basketball toss. You were a hotshot ball player in high school, supposedly. You were also super competitive.

A couple kids came over holding basketballs from the game.

“You can pull them out from underneath,” one said. “You don’t have to pay.”

“Yeah,” you said, “but then it doesn’t keep score, right?”

The kid stared off, passed his basketball from hand to hand.

“Which machine did you take that ball from?” you asked him.

He pointed at the one you stood in front of.

You held out your hand, made a beckoning motion for the ball. The kid handed it over. He looked defeated. I knew that look. It said, ‘I tried to help someone and got fucked over.’

“Good idea though, man,” I said. I brought up my fist for a bump. There was a second where he just looked at my fist. Like he wasn’t sure if he wanted to touch it. Another second passed – enough time to wonder if the little shit was really gonna me hanging.

But he didn’t, thank God. He balled up his fist and gave me a hesitant little bump.

Fuck yeah, brother.

At first I threw up bricks, one after another. I could see you from the corner of my eye, in the zone, knocking down baskets.

Then I made one.

Swish.

And another.

Swish.

I caught a rhythm, didn’t look down to pick up fresh balls, just locked in on the front of the rim and let my hands work their automatic magic.

Swish. Swish. Swish.

“Three, two, one,” the kid behind us announced.

The buzzer buzzed.

I looked at my score, at yours. I won, by one basket. You looked pissed.

“Again,” you said.

We inserted our prepaid arcade cards and the balls released.

Swish, my net went. Swish. Swish. Swish.

“Three, two, one,” the kid announced.

The buzzer buzzed.

I won, again. By one point, again. You looked pissed, again.

“One more,” you said.

I pointed at the card slot. “It says two fifty a game. We’re out of money.

“I’m getting more.”

Most of the balls were still free of the game’s lock, and I motioned to the kid, told him the balls were all his.

“Thanks,” he said, and started to toss them at the basket.

The balls went – Swish. Swish. Swish.

“Kid’s good,” I said and followed you to the kiosk, but right when you were about to slide your credit card, they announced our name.

Our lane was open.

It was time for the main event – bowling.

But I don’t want to talk about bowling.

What I want to talk about is the people dressed as animals in the next lane. Furries, they’re called.

We were assigned to the first of the regular walk-in lanes, and both teams in the league game next to us were fully geared up furries – dogs, a bear, a cute little wolf in a tutu, and all sorts of animals in the greater cat family.

Most of them seemed peaceful, but there was a faction wearing leather jackets and heavy chains and studded collars. One of the rough bunch was dressed as a fox with a spiky mohawk, completely immersed in his sly routine. I watched him sneak behind the bear furry, do the old tap-one-shoulder-but-stand-on-the-other-side. The bear’s head blocked his peripheral vision and he kept falling for it.

“I can’t keep my eyes off them,” I said while lacing up my sweet size twelve and a half shoes.

“They want you to watch,” you said.

The fox was onto other mischief, like stealing people’s beer and running a few steps away and pretending to drink them. All sly like.

“This guy is great,” I said.

And we bowled.

Everything was going pretty well, but a tiger from the furry crew kept crossing over onto our side. It wasn’t intentional or anything, but there were a few times where we were winding up to roll the ball and the tiger’s ass backed damn near into us and we’d have to give each other lame, embarrassed-to-be-dominated looks.

“Next time he does it, I’m gonna grab his tail,” you said.

“No. No way. You never grab an animal’s tail.”

“Watch me.”

I didn’t doubt you. I never doubted you.

Sure enough, the next time the tiger’s ass came pushing its way into our lane, you reached out and gave his tail a proper tug.

The tiger turned and said, “Hey! Did you just pull my tail? That’s not cool.”

“Then quit wagging it all over our lane,” you said.

“You never pull an animal’s tail,” said the tiger.

The cute little wolf furry came up beside the tiger and bent over in front of you, lifted her tutu and exposed her tail, swayed back and forth seductively to make it wag.

You giggled and gave the tail a tug.

The wolf put her hand over her mouth all bashful and skipped away giggling. You came and sat next to me, a grin across your face.

We watched a bulldog furry follow around the cute wolf and act theatrically jealous until the wolf finally relented and bent over and lifted her tutu. The bulldog gave her tail a tug.

The wolf straightened and hugged the bulldog, her head against his chest. She was tiny and looked safe in his arms. They stood together like that, slightly swaying to the melody of clattering pins.

“I like bowling,” you said, and interlaced your fingers in mine.

I lifted your hand and kissed the back of it.

“Me too.”

We were getting along really well just then.

Alex Rost runs a commercial printing press outside of Buffalo, NY

By William Schaff

William Schaff has been a working artist for over two decades. Known primarily for his mastery at album artwork, (Okkervil River, Godspeed You! Black Emperor, Mighty Mighty Bosstones, Songs: Ohia, etc.) Schaff is also the founder of Warren Rhode Island’s “Fort Foreclosure”. The building, lovingly named without the least bit of irony, serves as Schaff’s home and studio as well as home and meeting place for other artists (most notably former resident musicians MorganEve Swain, and the Late David Lamb, both of Brown Bird). William also performed for a decade with the What Cheer? Brigade, as one of 20 musicians in a brass band that travelled the U.S. and Europe. An experience that shaped so much of his life. In 2015, recognizing the importance of art in this world, he expanded his community to the West Coast, where he started “The Outpost”, in Oakland, California. There — financial earnings be damned! — William filled his days creating works of art for private commissions, bands, exhibitions and his own examinations of human interaction. He has since returned to Rhode Island and can be found, daily, doing the same at the Fort. He has a Patreon page if you’d like gifts in the mail and to help keep the lights on.

Adam Soldofsky is the author of the poetry collection Memory Foam, recipient of an American Book Award and Telepaphone, a novella. His latest collection, Three Short Novellas, will be available this Summer.

By Craig Rodgers

Craig Rodgers is the author of ten books, a handful of lies, and all manner of foolishness.