Jason Sebastion Russo interviews Bill Whitten.

JSR: I had a first draft of questions for you about our mutual friend OD’ing in your band’s hotel room one long ago evening at SXSW, but I felt it was too salacious, even though it ends with me walking past the hotel gym at dawn and seeing you lifting weights in a black t-shirt and pair of jeans. I was still wet from having given our friend (no Narcan in those days) an ice-cold shower. I also had a couple of false starts about seeing you play guitar with Shady at the Knitting Factory (where we were pointed out to each other but not introduced, and you told Grasshopper I looked like a “young Kerouac” much to my great pride). I also wrote the story of Grand Mal playing at the Rhinecliff Hotel—which ended with you rolling around that filthy all-ages room without a shirt, and passing out at my and the late John DeVries’ couch in Poughkeepsie. But these questions were all starting to head into Hubert Selby territory; debauchery, treachery, substance abuse etc. etc. Should we pursue such a line of discussion?

BW: I feel somewhat queasy directly discussing (without the screens of fiction or abstraction) tales of past depravity. It’s probably best to take the Wittgensteinian approach: What we cannot speak about, we must pass over in silence.

JSR: Fair enough. Ludwig missed his calling, imho. What is a central metaphor in your life? I’m obsessed with the image of a plant slowly growing toward a window, for example.

BW: Waking up drunk in an enormous, empty, windowless, dark, locked room in a stranger’s house. After a period of time (hours? days? who knows?) finally escaping. Penniless, walking for miles trying to find to my way home, vowing to change my ways, to begin again…

`

JSR: Word, or amen, to that. Do you have a common, almost trite, saying that you’ve thought to yourself most of your life? For example, I have been saying, “live by the sword, die by the sword” to myself my entire life. And/or, “garbage in, garbage, out.” Direct quotes from my father’s childhood in the Bronx. You?

BW: Again and again, the words of Divine come into my brain: Kill everyone, kill everyone right now.

JSR: An enduring, undeniable platform. We both lived in the same Brooklyn building for years, yet I was surprised that as soon as you left NYC, you immediately started writing and singing about exile. I get it now that I spend 80% of my time in central New York. I assume the shift in locale impacted your creative life. Can you describe how?

BW: Being something of a pessimist, I expected, from the moment of my arrival in New York (America’s insane asylum) in 1990, delivered from a Peter Pan bus into its cold, dingy glitter and trash-strewn streets and neighborhoods, that my stay would be short-lived. Back then (maybe now?), it was a city of fugitives, of pilgrims – men and women like me – on the run from their families, from themselves, from their origins. I navigated it according to maps I’d brought with me, drawn by its victims and castoffs. I was fascinated with both the strange, vacant-faced men crouched in dark doorways and the glamorous youth who arrived en masse from every corner of the world to take part in the vast, industrial form of human sacrifice known as the ‘arts scene’.

I have notes from the first party I ever went to in the City:

How to pay attention to her words when the muscles jumping in her jaw, the blue veins pulsing beneath her eyes were all clearly visible beneath her starveling’s translucent skin. She ran her hands through her hair, touched her nose, her ears. “I’ve become (mumble) fixated on the (mumble) fact that a kind of apocalyptic menace follows me around (mumble), the City is on the verge of destruction, I can feel it.”

I moved constantly from neighborhood to neighborhood, borough to borough, always in search of a cheap apartment. Whenever I found one, there would be constant rumors among the tenants about imminent eviction, about the landlord’s desire to sell the building to speculators. Expulsion from NYC was always inevitable.

In 2018, as I stood on the stoop of my apartment in Brooklyn for the last time, I wondered what real difference would there be between NYC and a city in the Midwest. No matter where you go everyone is glued to their phones (an apparatus designed to enslave it users). The restaurants serve the same food, the same coffee. The men have the same haircuts. True, the people are more beautiful in NYC… but the world has been flattened and everyone on it made the same.

In any case, my only plausible claim to exile is from the bookstores of NYC (currently as close to extinction as the Yangtze Finless Porpoise); my true homeland. How great it was going from bookstore to bookstore like a pub-crawl and discovering Roberto Calasso, Jacques Ellul, Bruce Chatwin, Mavis Gallant etc etc. Of course, there are a handful of bookstores where I live now but none pass my personal test (a pretty low standard) of what makes a halfway decent bookshop – i.e. it must carry titles by Marguerite Duras and Giorgio Agamben…

Finally, circling back to your question, leaving NYC has had no impact on my creative life. I continue to pursue a bad idea (a life devoted to making art) stubbornly and against all reason.

JSR: What percentage of the world is evil?

BW: An ever-growing percentage. But, I believe in apocatastasis i.e. universal salvation, which means that when we die we all go to heaven. So evil is of less importance if we all will spend eternity in paradise.

JSR: Can people change?

BW: People’s actions can change, which is all that matters.

JSR: Well said. What percent of your personality can you choose?

BW: The easy way out is to proclaim that humans are purely determined by exterior forces i.e. people are social constructions, and their personalities are fungible. But if you’ve ever witnessed the birth of a child, you know that they come equipped with an already existing personality or what people used to call a “soul”. So the correct answer is zero.

JSR: I helped you move out. You were the only friend that showed up to move me into my first NYC apartment. We were an excellent moving team, in fact, and did a ton of moving gigs together; always glad to combine working out with making rent. Why pay for a gym when you can get paid to be a mover? Bonus: being a furniture mover is one of the best ways to get to know the five boroughs of NYC.

I spent a lot of time on your stoop before it became my stoop too. Before I finagled my way into the top-floor apartment of our building—no small task—thanks in part to you and Parker Kindred (one of the best drummers alive, who’s played with everyone from Lou Reed to Jeff Buckley to Cass McCombs etc). Something Parker probably regretted when I added to the guitar overdubbing, kick drum sampling, bass rehearsals competing in the hallway, the first time I dropped an amplified bass guitar on my floor/his ceiling. Ours was the kind of building that a body dropping past the window would have been noteworthy but not that shocking.

Our stoop was one of those easy-to-mythologize places like a Sesame Street set or Scorsese b-roll. During that very specific era of Brooklyn, at the decline of its vitality, in the heart of doomed Williamsburg. Thanks to our sweet landlady’s charity, we got a front seat to Rome’s burning. (“How will they be able to afford milk?” was how she explained keeping her tenant’s rent at one-third neighborhood’s market value.) We stocked the building with bandmates and friends, all of us touring and recording as the music industry turned to dust beneath us. Thank God you guys got me in. I was indeed running from the Minotaur, having just been evicted from my tiny basement apartment around the corner, in a building sold to developers by the owner’s son. Developers that turned it into a condo overnight. I was only homeless for a month before you and Parker convinced our landlady that I was good people… you threw a rope and hauled me up to safety.

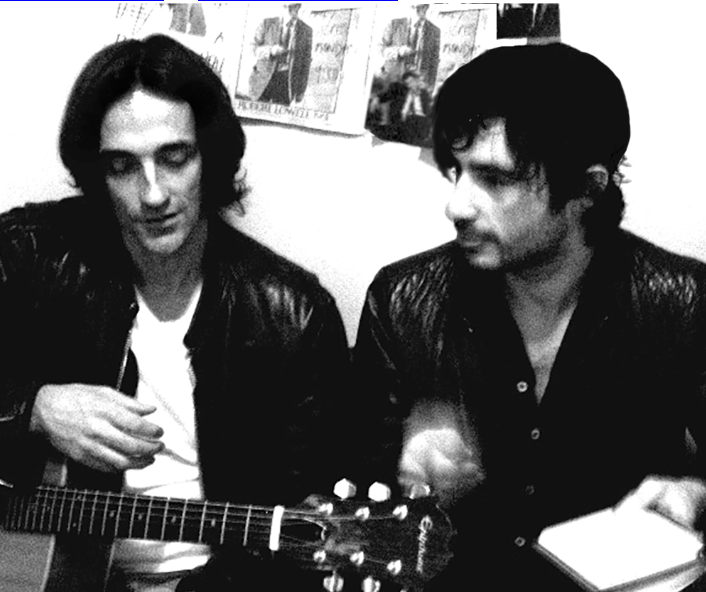

I think some of my favorite stoop moments were your and Ken Griffin’s (Rollerskate Skinny, Favourite Sons, August Wells) endless debates. We’d gather around like Athenians and discuss books, film, music, television, romance, drugs, religion, politics, metaphysics. Everyone in our building was or had been in a band that I’d been a fan of prior, and it was nice to be amongst musicians that didn’t only want to talk about guitar pedals. So, here is my question: did our tight-knit cadre of NYC friends/reprobates impact your creative life in any way? Other than the obvious fact that you were constantly luring us to your living room to track vocals or guitars.

BW: More than one woman commented that our building resembled a barracks, or a halfway house for aging rock musicians or some kind of disreputable all-male commune. Of course, for me, my fellow ‘inmates’ were an enormous influence. Yes, I did get everyone (including yourself) in the building to play and sing on my albums Clandestine Songs and Burn My Letters. Collaborating with friends is an incredibly intimate, somewhat risky venture that requires trust and generosity. As the lockdown taught the world, interacting regularly with friends is indispensable and beneficial to the body and soul. I learned a lot from everyone and miss them all. Not a day goes by that I don’t wish I could sit down and have a cup of coffee with one of you guys. It goes without saying that texting and emailing and zooming are not in any way commensurate with in-person interaction.

JSR: Why do you get out of bed in the morning?

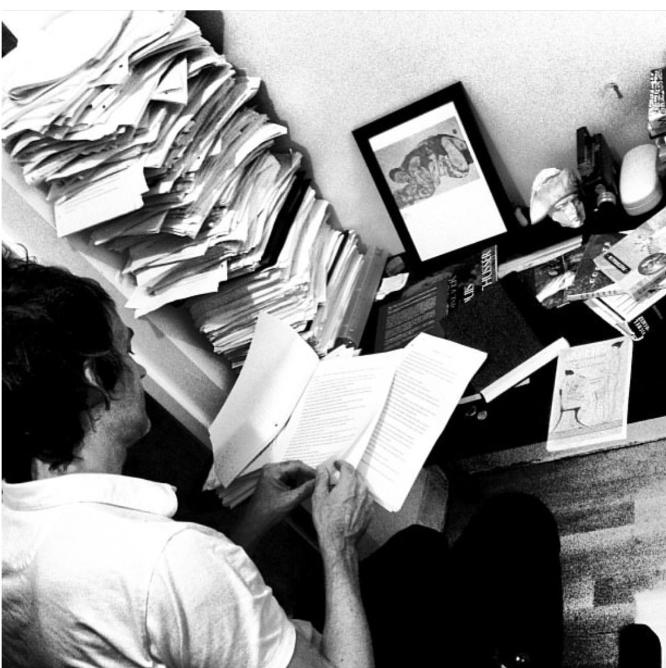

BW: To drink coffee, read, write, plot.

JSR: Is everything singular or plural?

BW: To believe everything is singular, you’d have to be a Spinozaist (a Pantheist) and believe God was/is everything; trees, dirt, air etc. Against this idea of a monad as the totality of all things, there is the transcendent, for example, Christ (a being not part of our material world) exploding out of eternity, desacralizing the world, ending animism. I prefer the latter to the former. Lately I’ve been thinking that interdimensional Ufo’s rising out of the ocean/descending from the stars and acting as divine intercessors to prevent nuclear war…could fulfill a similar function.

JSR: Would you choose to live again without knowing you were given a choice, if you had the choice?

BW: Yes. The prime directive of every living creature is to persist by any means necessary.

JSR: Is belief in God a choice?

BW: Not when someone is pointing a gun at you or punching you in the head or you’re suspended in that prolonged interval of time called a car crash. In those situations, appeals to god come forth unbidden from one’s lips. You realize (and then if you survive, forget) you’ve always been a believer.

JSR: Which percentage of utility have you lost from the internet?

BW: In 2023, everyone is brain-damaged. Paul Virilio was often attacked for being too pessimistic or even reactionary when he detailed, way back in the ‘90s and early ‘oughts, all the damage that technology – by marooning in us in an eternal present – had rendered upon our senses. In America, 54% of the population now reads below the 6th-grade level. We can’t see, think, remember, move, write, or talk as we once did. And we’re all under 24/7 surveillance.

JSR: Is it safe to say music was your primary pursuit at the beginning of your creative life? Why or how did it surpass writing? And where is that balance now? Do you feel the same amount of excitement about both? Does one eclipse the other?

BW: I wrote when I was a kid and hid my stories in my underwear drawer. But writing was always unsatisfying and deeply shameful. I didn’t really want anyone to know my thoughts. I picked up a guitar pretty late, around age 23 or 24, driven to provide accompaniment to the songs that were (are) banging around in my head. Kandinsky described the compulsion to create an ‘inner necessity’, which sounds right to me. Whether I write or play music on any given day is dictated by the fact that I live in a small house with my family. Making music is noisy and disruptive, while typing into a 2008 Macbook is not. In some ways, these activities seem pretty much the same to me – they involve the constant erasure of bad ideas.

JSR: Can you describe the very early years when you were forming St. Johnny, and you were roommates with Dave Baker and bandmates withHartford Grasshopper? The stories I’ve heard remind me of living with John Devries in Poughkeepsie, where I apprenticed under Agitpop and Cellophane, incubated Hopewell, and got involved with Mercury Rev., which is to say, total chaos. What pushed you forward? How did you escape the chaos and make it to the big city? Music?

BW: Growing up, the key idea I learned from books, magazines, film was that all the best musicians and writers were insane, and they lived as outcasts on the margins of society. When I developed an ambition to be a rock musician, the first thing I did was try to become like the people I’d read about. As if a curse had been placed on me, I took Johnny Thunders as my role model. Naturally, I tried to find others who had similar interests. I moved to the nearest city – Hartford. I put an ad in a local ‘arts’ newspaper – “William Burroughs-style bassist wanted”. Grasshopper answered. He was working as a court reporter in Hartford and divided his time between there and Upstate New York, where he and the other members of Mercury Rev were working on Yerself is Steam. He played bass for a while in a nascent version of St. Johnny before disappearing (I learned of his departure from the note he left under the windshield wipers of my Chevy Nova) to go on tour with the Flaming Lips as their ‘lighting and explosives’ technician. Unlike myself, he was a college graduate and had a greater knowledge of music, film, and literature than I did, and his influence on me was not trivial. He eventually moved to NYC, I followed not long after, eventually landing in an apartment in Carroll Gardens with his bandmate Dave Baker. In those days (early 1990s), I was a terrible roommate. Evidence of this can be found written on the inside back cover of one of the books (Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty) I purchased around that time: 1) A man can never really know a woman, he can only pursue her indefinitely. 2) My musical instruments are razorblades that leave wounds on my body. 3) These wounds are the aesthetic models for my music. 4) My music is filled with hidden holes. 5) Things left out (the holes) are as important as what remains.

Bolano wrote in Savage Detectives: We were spectral figures, on whom you wouldn’t dwell at length without turning away. It is a nice description of my friends and I at that time…

JSR: That reminds me. I found your copy of Bolano’s Distant Star when I moved, I swore to return it, and one day I will. Glad you mention those holes; that’s a good way to describe a distinction I loosely subscribe to, that there are two kinds of creative people: negators and cheerleaders. Both are generative, though negators rely more on preventing or removing what doesn’t work. Discernment is central to the process. I’m married to an incredible negator that makes a fine film editor as a result, and I usually partner up with them creatively when I partner up at all. I require them to sift through the sheer amount of crap that I, a cheerleader, am always swept up in. I used to outsource a lot of my discernment to you, arriving in your kitchen stoked on a dozen ideas about all manner of everything, and you’d weigh in, reliably. It’s the case with many negators that they would never make or release anything if they didn’t work with a cheerleader. So, both sides of the coin have their merits. My creative relationship with Justin (younger brother and frontperson to the very amazing Silent League) is emblematic of my theory. He kept me in check, and I made sure he released things and had content to play with. I’m using some hyperbole here to make a point because of course he generates content on his own, and I am able to cut things. It’s more of an orientation than a hard and fast rule. Would you say your aesthetic sensibility relies on discernment?

BW: I’ve never been smart enough to have an aesthetic. My goal is usually: try to create something that does not make me ashamed or want to blow my brains out after playback or re-reading.

JSR: Has having a family changed or cemented your worldview?

BW: Christopher Lasch once said: a parent looks at the world and all its events in the darkest possible light. Deep pessimism and rage are feelings I experience every day. I’ve never known a more sinister time than the time we live in now.

JSR: Another important marker, I think, is when I started hearing barroom piano bounce off the wall of the building behind ours. Instead of electric guitars. It provided a soundtrack to the building’s bathrooms, all situated in the back of our apartments. You serenaded us all. Happily, you bequeathed that creaky old thing to Chuck Davis and me, and I’m staring at it while I type this. It’s the sound of your William Carlos Whitten records, some of the finest rock music ever made, in my opinion, ragged, dignified, and mastered to perfection by our old pal Dave Fridmann. A perfect third act to your musical legacy.

BW: In 2008, someone from Our Lady of Mt. Carmel on N.8th Street left a perfectly good upright piano on the curb. Incredibly, our mutual friends Kenneth Zoran Curwood and Adam Marnie put it on a pair of skateboards and wheeled it four blocks to my apartment. Luckily I lived on the first floor. I’m an autodidact in all things and thus completely self-taught when it comes to the piano, and naturally, play it all wrong like an aphasic chimpanzee. To me, my piano is the black monolith at the beginning of 2001: A Space Odyssey. When someone who can actually play a piano comes over to my house and unleashes all the magic stored within it – it’s always leaves me stunned, amazed. As a side note, I’ve always had ambivalent relationships with musical instruments. My piano has never been tuned, I’ve only ever owned cheap, barely functional guitars. All my gear – recording devices, pre-amps, guitar amps, and effects, the computer I’m writing on now – are usually half broken and on their last legs.

JSR: You and I subscribe to the same school when it comes to gear. My guitar tone depends on what pedals are discarded or forgotten by other players in the rehearsal space. The people that can afford really nice guitars are generally not the people who create music. But beyond all that, crappy gear is a form of limitation. Of boundaries. Which, as I get older, I realize is one of the most important aspects of the creative process.

I remember being handed a leaflet or missalette at a St. Johnny show- maybe at the Mercury Lounge or the old Knitting Factory- that was kind of a zine of your writing, which read like William Burroughs in my memory. Did they pre-date the band? Had you always been writing them? Care to describe what you were writing back then?

BW: I don’t remember, lol, and I regret the enormous influence William Burroughs (a pedophile and murderer) had on my life. I should have been reading Proust or Leopardi! The Beat Generation was a psyop! What a waste! Haha!

JSR: The Beat Generation is basically a dorm room poster at this point. Speaking of psyops…do you think the post-Nirvana-1990s indie rock explosion, which we were both part of, was a psyop?

BW: If it was a psyop, what would the goal have been? To transform (in tandem with other cultural engineering projects) the population of the West into solipsistic, nihilistic, porn-addicted drug-takers, incapable of reading a book or watching a film in its entirety, compelled to stare helplessly at electronic devices 20 hours a day while fulfilling their role as the world’s consumer of last resort? Is there a clear trajectory from Kurt Cobain to the Strokes to Occupy Wall Street…and then…to Bernie Sanders and AOC advocating for vax mandates and nuclear war with Russia? Was/is Williamsburg, Brooklyn a CIA outpost, a Bermuda Triangle of transhumanist-mind-control-pseudo-left-lifestyle politics?

¯\_(ツ)_/¯…

Bill Whitten has written a book called BRUTES and recorded many albums.